Frederick Justen (1832-1906), working at Soho-based Dulau & Co. booksellers, produced different sets of caricatures from the Franco-Prussian and the Commune (1870-71), including some at Cambridge University Library, at the British Library and Heidelberg University Library. A close inspection of one of the prints in the sixth and final volume of Cambridge University Library’s 1870/71 caricatures (KF.3.9-14) shows the challenges raised by the identification of the subjects of the caricatures and suggests that Justen updated the collection as late as October 1878. Digitised in late 2020 and the subject of an online display, some of these prints are currently exhibited in the Modern and Medieval Languages and Linguistics Library. One of the particularly interesting facets of this collection is the existence of similar sets, all produced by Justen. Despite sharing the same red binding, title page and 1872 article from the Atheneum advertising the sets, the various Justen collections are not identical. This diversity provides ample room for investigation, and one entry point is the case of an Italian print in Cambridge’s sixth volume entitled ‘Il Gallo di Alfredo il Piccolo’, which appears to have been printed much later than any other print found in this compilation.

‘Il Gallo’ seems congruent with the rest of the collection at first glance. It shares a visual aesthetic with much of the 1870/71 imagery, and though it is the sole Italian print in the Cambridge volumes, Italian prints feature in other Justen collections. For instance, the British Library’s eighth and Heidelberg’s seventh volumes both hold some Franco-Prussian War-related satirical prints by Antonio Manangaro (1842-1920) cut from Neapolitan journal Stenterello. This demonstrates not only that Justen was able to source Italian satirical prints, but also that he repeatedly considered such material to fit into his 1870/71 collections thematically, even though Italy was only an indirect participant in the conflict.

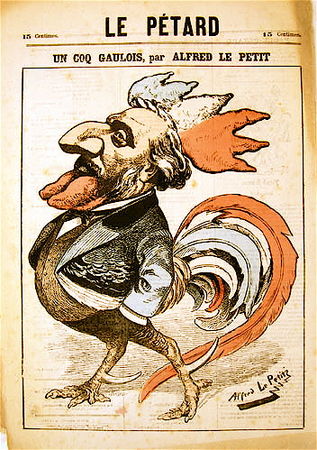

The depiction in ‘Il Gallo’ of Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, Hungarian statesman Gyula Andrássy and Russian Foreign Minister Aleksandr Mikhaylovich, Prince Gorchakov, three actors prominent on the European political landscape during 1870/71, further suggests a shared timeframe with the rest of the collection. Finally, the title’s reference to ‘Alfredo il Piccolo’ (or, Alfred Lepetit, 1841-1909), a prolific caricaturist in Paris during 1870/71, makes the dating of this print appear to be a formality.

Because of these considerations, it had been reasoned that the rooster at the centre of ‘Il Gallo di Alfredo il Piccolo’ could be a depiction of Giuseppe Garibaldi by Lepetit. Garibaldi was arguably Italy’s most internationally recognisable figure at the time and was an active participant in the Franco-Prussian War, fighting on the French side as a commander of the Army of the Vosges. Moreover, he is the subject of other prints during 1870/71. Underneath the image is the caption ‘Quando questi astri saranno tramontati il canto del gallo si sentí per tutto il mondo’ (‘When these stars have set, the crowing of the rooster will be heard throughout the world’). If we take this image to depict Garibaldi during the Franco-Prussian War, we might assume the falling stars – here, the three European statesmen aligned against Garibaldi, and thus, the French – are representations of a European system which is currently balanced against France and Italy, which might one day fall to this rising Franco-Italian alliance during 1870/71.

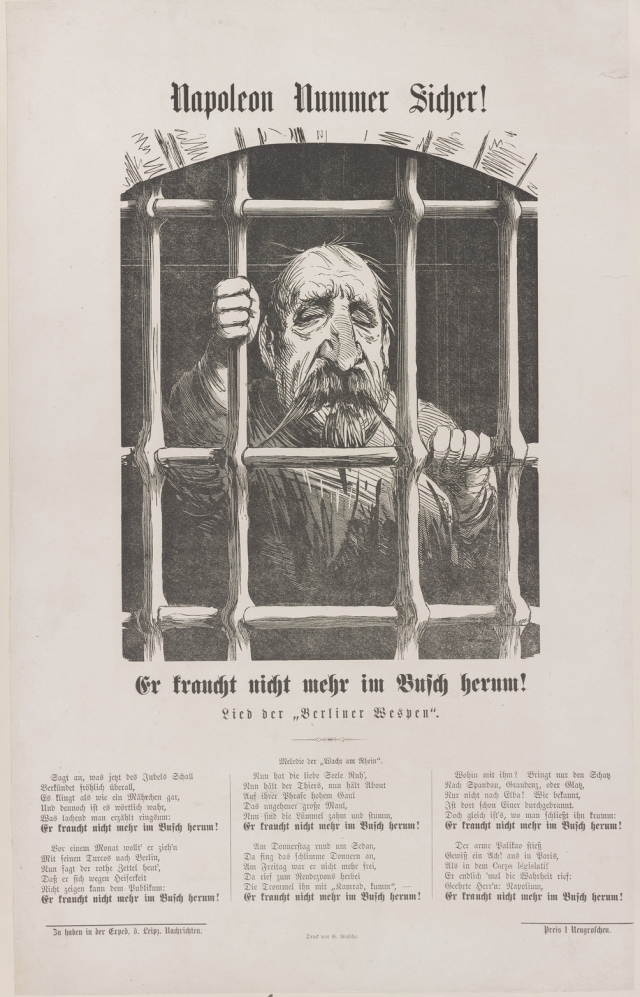

Loose ends pull at this interpretation, however. First is the structuring of the sixth volume itself. The final pages are unlike the ordered and numerically coherent prints which precede them. Most of the volume is dedicated to three complete German caricature sets: Zündnadeln (Darmstadt), Humoristisches Kriegs-Album (Hamburg) and Humoristiches-satyristisches Kriegs-Album (Elberfeld, part of what is now Wuppertal). Thereafter, the final few prints are a little more discorded numerically and thematically. We have numbers 22 and 25 of Der Krieg in Bildern (Stuttgart, Berlin) taken from a larger body of 25 ‘realist’ war prints, which only the British Library’s Justen collections seems to have numerically complete; one single page from London’s Fun magazine (1861-1901) concerning the Paris Commune, and a single-sheet caricature printed in Leipzig mocking Napoleon III after the fall of the Second Empire. This raises the possibility that Justen added some extra pages for spares he accumulated during his time collecting this set.

As for the provenance of ‘Il Gallo di Alfredo il Piccolo’, the small title ‘Papagallo no. 40’ just to the left of the crest of the rooster reveals the origin of the print: Il Papagallo, a satirical magazine produced in Bologna between 1873-1915. Upon close inspection with the Cambridge Digital Library tool, one can make out the printed impression of a title page on the reverse of the print. This confirms ‘Il Gallo’ to be from an edition of Il Papagallo and adds a date of publication: 6 October 1878 – more than seven years after the end of the Commune in May 1871.

This prompts several questions. First, if not a picture of Garibaldi fighting on behalf of France in the Franco-Prussian War, who is ‘Il Gallo’, and what is the print in reference to? The date provides a piece of the puzzle. The Congress of Berlin (June – July 1878) held in the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War is one possibility given the presence of Bismarck, Andrássy and Gorchakov as representatives for their respective nations at the Congress. In Italy, the conference was regarded as a failure due to the lack of relative territorial gains in the Balkans while Austria gained a protectorate over Bosnia and Herzegovina (Smith, Italy and its Monarchy, pp. 75-76). The nation had formed a new government in March 1878 under the aegis of Prime Minister Benedetto Cairoli (1825-1889). Cairoli bears a striking resemblance to the cockerel – down to the dashing moustache and goatee combination – and his apparent Francophile politics further imply he is likely the central figure of the print. The Italian representative for Cairoli’s government at the Congress was Foreign Affairs Minister was Count Luigi Corti (1823-1888), whose name we find on a dandelion to the left of ‘Il Gallo’, another clue that this print concerns the Berlin Congress.

Additional aspects of ‘Il Gallo’ strengthen the case for this interpretation. To the left of the cockerel, we find a snail labelled ‘Beaconsfield’. This is a reference to the Earl of Beaconsfield, a title given to British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), who was amongst the British representatives at the Congress. His depiction as a snail is a possible reference to apparent British indecisiveness on the issue of Russian expansion throughout the late 1870s, though historian Otto Pflanze argues that Disraeli was ‘after Bismarck the most impressive figure at the Congress… he [Disraeli] advanced British interests with force and skill’ (Pflanze, Bismarck and the Development of Germany, Vol. II, p. 439).

Other aspects of the image are harder to identify. The three stars are falling towards a group of hooded men which almost resemble a mountain range, perhaps a reference to the topographic setting of the Balkans and Turkey which are the key points of interest during the Congress. The hoods of three of these men have labels, though what these descriptions read is difficult to discern. The most legible of these, just under the head of Andrássy, appears to read ‘Ultramontanismo’ (ultramontanism): a doctrine of Papal superiority over those of the state or nation. Following the incorporation of Rome into the nation state of Italy in 1870, ultramontanism lost much of its impetus. Could the falling of stars into this rocky landscape therefore be not only about specific political figures but entire political ideologies? If this is the case, could the illegibility of the labels be purposeful: a visual device to imply their metaphorical erosion from the political landscape?

A second clue is the mention of Alfredo di Piccolo/Alfred Lepetit. Lepetit was amongst the most prolific caricaturists in the final third of the nineteenth century, contributing to several satirical journals and setting up a few of his own. This includes the creation of Le Pétard in 1877, which in December that year published the image ‘Un Coq Gaulois’. This version depicts French politician Leon Gambetta as a tricoloured cockerel, a probable reference to Gambetta’s involvement in rallying support against the government headed by Franco-Prussian War veteran and then-French President Patrice de MacMahon during the Crisis of 1877. The term ‘Gaulois’ in the title is possibly a reference to the ideology of Gallicanism: the effective inverse of ultramontanism, and though this specific reference is missing from Papagallo’s ‘Il Gallo’, the repeating of the cockerel motifs and the labelling of ‘ultramontanismo’ might suggest some political feeling has been carried over from Paris to Bologna.

Deeper investigation into the meaning of the print is hard to discern as a standalone image: ‘Il Gallo di Alfredo il Piccolo’ would be clearer with its accompanying article or other images from Papagallo. The print was produced months after the end of the Berlin Congress, and it is difficult to discern whether the print is hopeful for an Italian-dominated future, or whether ‘Il Gallo’ is an ironic twist on Lepetit’s original, made to mock the Cairoli government’s passivity in waiting for the established stars of European diplomacy to fall. Regardless, the reproduction of similar visual motifs from Paris to Bologna is an interesting take away from the image in itself, providing further evidence that caricaturists in this period consumed and engaged with works published across national borders.

Moving beyond the immediate implications of ‘Il Gallo’, we are left with an equally important and provocative question: why did Justen consider this image to fit thematically with the rest of his collection? It would be easy to say that it was simply a spare he wanted to put somewhere to preserve what is a particularly stunning print. However, Justen repeats this practice in other collections. For example, in the final pages of Heidelberg’s eighth volume there are three prints taken from Fun: one from October 1872, and a further two from February and September 1873, each of which concern Franco-German relations in the aftermath of the War and the Commune. It therefore seems unlikely this was solely an endeavour to preserve materials.

One rationale is that Justen accumulated materials which suited multiple collections across different collecting endeavours. The prints from Fun found in Heidelberg’s eighth volume could have been sourced during his curation of a three-volume set entitled Napoléon III devant la presse contemporaine en 1873 (British Library, 1764.c.21) donated to what was then the British Museum. As for accounting for the presence of ‘Il Gallo’ in Cambridge’s 1870/71 collections, sets donated to both the British Museum and Cambridge University Library by Justen entitled Pio Nono e la stampa contemporanea nel 1878 (CUL, KF.3.1-8) may be the best lead. These eight tomes are filled with clippings of newspaper reports which concern the death of Pope Pius IX in February 1878. The first few focus on Italy, including reports from hundreds of news outlets from Ancona to Vicenza. The rest contain reports from major cities further afield, from New York to Moscow, including Scandinavian and Baltic newspapers, as well as a host from cities in Germany, France, Spain and Britain. Though this collection does have several newspapers from Bologna, there is nothing from Il Papagallo; however, most material in the ‘Pio Nono’ collections are serious documentary reportage, in contrast to the colourful whimsy of ‘Il Gallo’. It is possible that Justen may have therefore considered the print to not be in keeping with the tone of the rest of the ‘Pio Nono’ collection and thus omitted it.

This leaves us with the final question, then: why did Justen feel ‘Il Gallo di Alfredo di Piccolo’ fit with his 1870/71 collections at Cambridge? The conclusive answer will likely never be more than speculation. That it concerns European power dynamics in a post-Franco-Prussian War is one rationale: Bismarck, Andrássy and Gorchakov continued to play an important role in forging and symbolising the dynamics of diplomatic power several years after the end of the Franco-Prussian War. Perhaps Justen envisioned ‘Il Gallo’ as belonging to the same era as the prints of 1870/71? Whatever the reason, the Justen collections continue to provide fascinating insights into not only the artists of the collection, but also the mind and choices of its prolific and meticulous collector.

Anthony Chapman-Joy

References:

- Morna Daniels, ‘Caricatures from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the Paris Commune’ Electronic British Library Journal (2005), pp. 1-19.

- Irène Fabry-Tehranchi, ‘Frederick Justen and L’Éclipse: the early 20th c. donation of 1870-71 Franco-Prussian caricatures and satirical magazines to Cambridge UL’, European Languages Across Borders (2020).

- Irène Fabry-Tehranchi, ‘Des jeux dans les collections de la guerre franco-prussienne et de la Commune, 1870-1871’, Les éphémères imprimés et l’image: Histoire et patrimonialisation, Florence Ferran, Bertrand Tillier (eds.) (Dijon: Editions universitaires de Dijon, 2023), pp. 21-36, available on Apollo and at C202.b.8251.

- Bettina Müller, ‘The Collections of French caricatures in Heidelberg: The English connection’, FSLG Annual Review issue 8 (2011-2012), pp. 39-42.

- Otto Pflanze, Bismarck and the Development of Germany, Volume II: The Period of Consolidation, 1871-1880 (Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 2014 (1990)) 571:55.c.95.42, LSF and ebook.

- Denis Mack Smith, Italy and its Monarchy (New Haven (CT): Yale University Press, 1989), 580:1.c.95.124 and 1993.9.2239