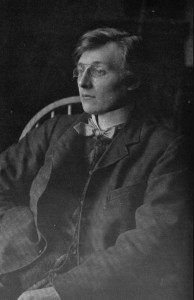

Have you ever noticed the Gordon Craig Theatre when travelling through Stevenage station and wondered who Gordon Craig was? I did and after a quick search on my phone it was soon apparent that this was a figure with an interesting and complex life worth writing about. Born in Stevenage (hence the theatre being named after him), Gordon Craig (1872-1966) was the son of the famous actress Ellen Terry, and as a young man he too was an actor alongside his mother in Henry Irving’s company. Much of his later work related to the theatre – stage designs, directing and writing widely on the theatre – but he also produced woodcuts and bookplates. This blog post will explore some aspects of his life and work using the UL’s rich collections.

After a brief acting career Craig gave it up in the 1890s and turned to art, learning how to engrave and do woodcuts from his friend William Nicholson (father of the better known artist Ben Nicholson). In his 1924 book Woodcuts and some words (Lib.6.92.213) Craig remembered this time, saying “From 1898 to 1901 I was cutting boxwood all day.” Early works included Henry Irving, Ellen Terry: a book of portraits (Lib.3.89.325) and his Book of penny toys (1900.12.8), both appearing in 1899:

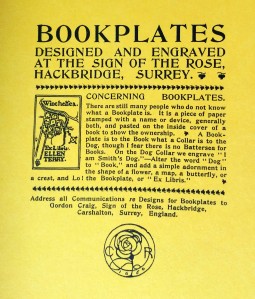

Craig designed bookplates for family and friends and anyone who commissioned one. His bookplates were gathered in a 1924 book Nothing, or, The bookplate (874.b.47). Many were very small and understated as he believed “That is what a bookplate should be – a gem. It should make itself small. It should be well set, quiet, and should announce whose book it is, and all in as few words and lines as possible.” The UL also has a 1997 Bookplate Society edition of his bookplates with a rather lovely advert for them displayed on the back cover.

Craig designed bookplates for family and friends and anyone who commissioned one. His bookplates were gathered in a 1924 book Nothing, or, The bookplate (874.b.47). Many were very small and understated as he believed “That is what a bookplate should be – a gem. It should make itself small. It should be well set, quiet, and should announce whose book it is, and all in as few words and lines as possible.” The UL also has a 1997 Bookplate Society edition of his bookplates with a rather lovely advert for them displayed on the back cover.

Returning to his 1924 book of woodcuts these are three of my favourites which show continued connections with the theatre:

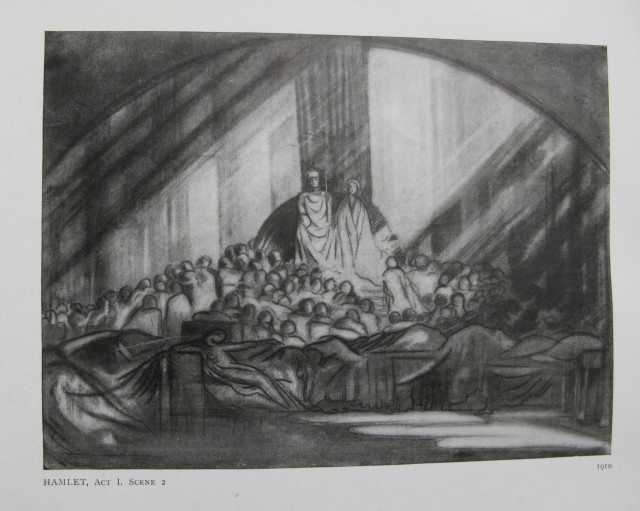

Perhaps the pinnacle of Craig’s illustration work was his contribution to Harry Graf Kessler’s Cranach Press edition of Hamlet, a monumental book which came out in German in 1928 and English in 1930. Our copy of the English edition (F193.a.1.1) was presented to the UL by Kessler in 1931. These images give a flavour of the work:

The woodcut here of the court at Elsinore in Act 1 Scene 2 echoes Craig’s design featured in his 1913 book Towards a new theatre: forty designs for stage scenes with critical notes (Lib.3.91.193) which in turn was from the influential 1911 Moscow Art Theatre production in which Craig collaborated with Stanislavski, one of very few of Craig’s projects that came to fruition. More on this can be found in Gordon Craig’s Moscow Hamlet: a reconstruction by Laurence Senelick (724.c.98.81).

Another book of set designs, Scene (Lib.3.92.201), came out in 1923 with a foreword by John Masefield. It is clear that Masefield was impressed by Craig’s work but he also referred to how little of Craig’s work appeared in theatres:

Another book of set designs, Scene (Lib.3.92.201), came out in 1923 with a foreword by John Masefield. It is clear that Masefield was impressed by Craig’s work but he also referred to how little of Craig’s work appeared in theatres:

While Craig may not have been involved in theatre in a practical sense, he contributed much to the theory of theatre in a number of works. The 1905 essay The art of the theatre (S950.c.9.320) took the form of a conversation between a playgoer and a stage director. For a number of years he produced a theatrical journal called The Mask (reissue at T415.a.1.1-14). In Ellen Terry, spheres of influence (415:2.c.201.68) J. Michael Walton points out that “a majority of the essays, notes and book reviews within The Mask are by Craig himself. He wrote responses to his own articles and even reviewed his own books. Most of it was quite blatant, much tongue in cheek, but it has brought him into question as any kind of serious critic.” Walton also edited Craig on theatre (9002.d.9877) which brings together a cross-section of Craig’s most significant writings.

While Craig may not have been involved in theatre in a practical sense, he contributed much to the theory of theatre in a number of works. The 1905 essay The art of the theatre (S950.c.9.320) took the form of a conversation between a playgoer and a stage director. For a number of years he produced a theatrical journal called The Mask (reissue at T415.a.1.1-14). In Ellen Terry, spheres of influence (415:2.c.201.68) J. Michael Walton points out that “a majority of the essays, notes and book reviews within The Mask are by Craig himself. He wrote responses to his own articles and even reviewed his own books. Most of it was quite blatant, much tongue in cheek, but it has brought him into question as any kind of serious critic.” Walton also edited Craig on theatre (9002.d.9877) which brings together a cross-section of Craig’s most significant writings.

Craig’s personal life was complicated (unsurprisingly perhaps after a childhood that was somewhat dysfunctional). In his memoirs of his early years, Index to the story of my days: some memoirs of Edward Gordon Craig, 1872-1907 (S415.c.95.23), he wrote “I am eighty-five. This is just the age when one can look into oneself and consider one’s defects”, proceeding to list eleven, the fourth of which was being excessively attracted sexually by women. Michael Holroyd, in his very readable A strange eventful history: the dramatic lives of Ellen Terry, Henry Irving and their remarkable families mentions thirteen children with eight different mothers, the most famous of which was the dancer Isadora Duncan. Their daughter Deirdre sadly died aged seven in an accident in Paris (Craig did not attend the funeral). The romance between Craig and Duncan is documented in “Your Isadora”: the love story of Isadora Duncan & Gordon Craig (415.c.97.293) which contains more than 200 letters from her.

Almost 60 years after his death Gordon Craig’s name is not a well-known one outside theatre circles but interest in him remains high. In 2010, for instance, an exhibition of his artwork was held. We have the exhibition catalogue, Edward Gordon Craig, 1872-1966: avant-garde theatre designer and artist with a foreword by his granddaughter Helen Craig (herself an illustrator best known for the children’s character Angelina Ballerina). In 2025 Craig will also feature in a new David Hare play, Grace Pervades which will explore the story of Irving, Terry and her children.

Almost 60 years after his death Gordon Craig’s name is not a well-known one outside theatre circles but interest in him remains high. In 2010, for instance, an exhibition of his artwork was held. We have the exhibition catalogue, Edward Gordon Craig, 1872-1966: avant-garde theatre designer and artist with a foreword by his granddaughter Helen Craig (herself an illustrator best known for the children’s character Angelina Ballerina). In 2025 Craig will also feature in a new David Hare play, Grace Pervades which will explore the story of Irving, Terry and her children.

Writing in Ellen Terry, spheres of influence (415:2.c.201.68) Michael Holroyd and J. Michael Walton both addressed how difficult Craig could be:

- Holroyd: “His work was uneven and his judgment erratic. Reading his books is an infuriating business. He is pretentious, stimulating, tedious, charming, oppressive”

- Walton: “Craig’s case was not helped by a tendency to exaggerate and a refusal to compromise. That, principally, is why his practical collaborations so seldom bore fruit. People got fed up with him. Plans to work with him … fell through”

However, Holroyd suggested that now is the time for a reassessment and asserted that “the contemporary visual arts have a great deal for which to thank Craig.” Craig’s son, Edward, agreed. In his 1968 biography, Gordon Craig: the story of his life (415.c.96.359) he recognised that his father was by no means perfect but was nevertheless an influential figure:

Whatever faults Gordon Craig may have had, whatever his deception, however thoughtless he may have been in his treatment of people, one thing will for ever redeem his character: the inspiration he gave to others.

Katharine Dicks