The one-year project Spanish chapbooks 1700-1900 in CUDL: dating ephemeral literature, made possible by a Cambridge Humanities Research Grant (CHRG) with the support of Cambridge Digital Humanities, has come to an end (see our earlier blog post on the project here).

Continue reading “Dating Spanish chapbooks: preliminary findings of a Digital Humanities project”Tag: Spain

The visitors’ album of María Luisa Aub : a hidden treasure

The visitors’ album of María Luisa Aub came to the University Library in 2018. María Luisa (1927-2013), affectionally called “Mimín” by family and friends, was the eldest daughter of Mexican-Spanish writer Max Aub. She had close links to Cambridge, having lived in the city for over 25 years, but she also lived in exile in Mexico for many years.

Continue reading “The visitors’ album of María Luisa Aub : a hidden treasure”Dating Spanish chapbooks: the wonders of artificial intelligence

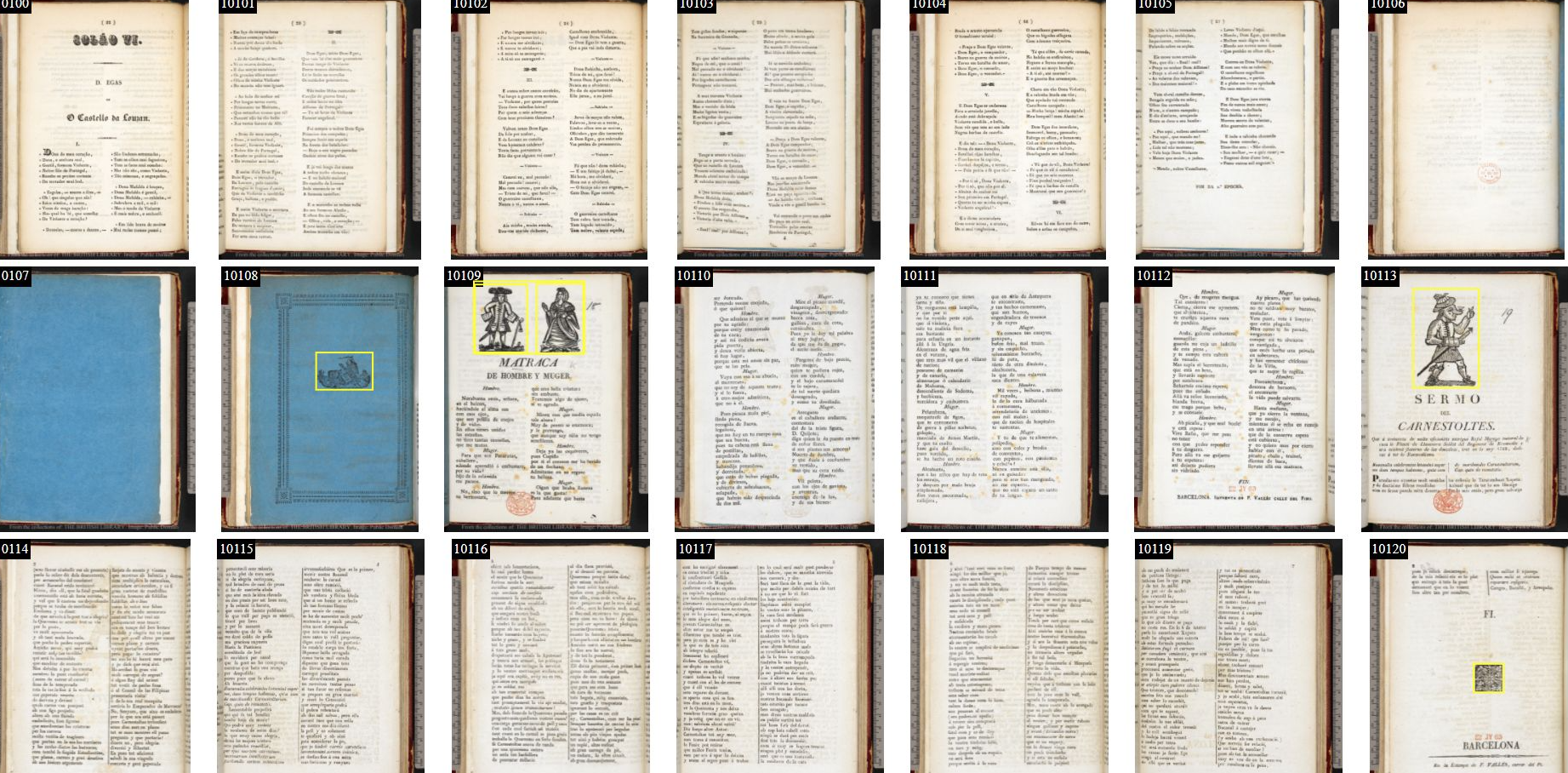

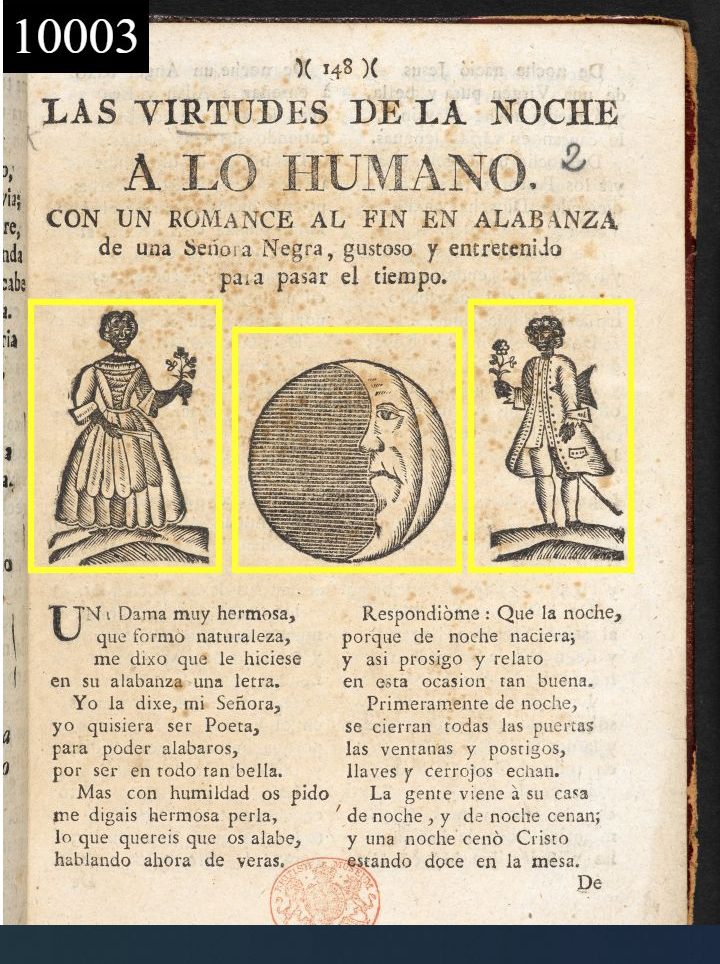

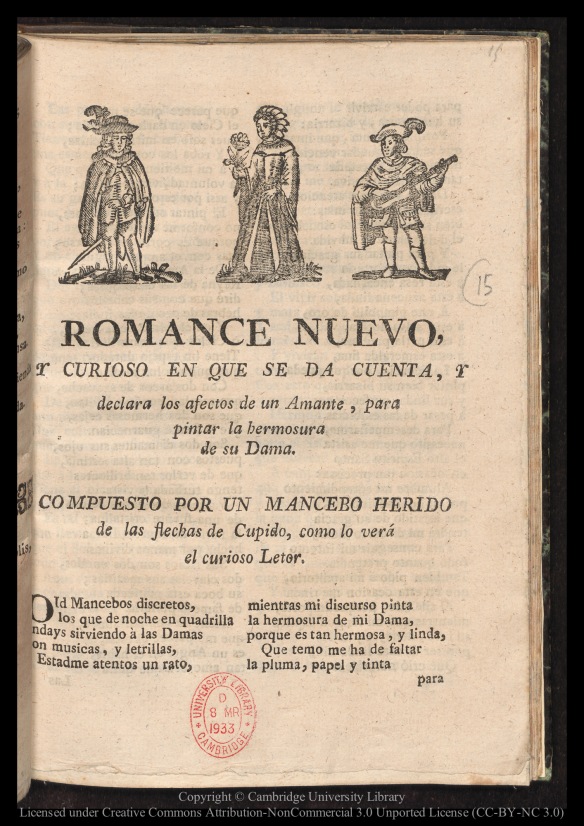

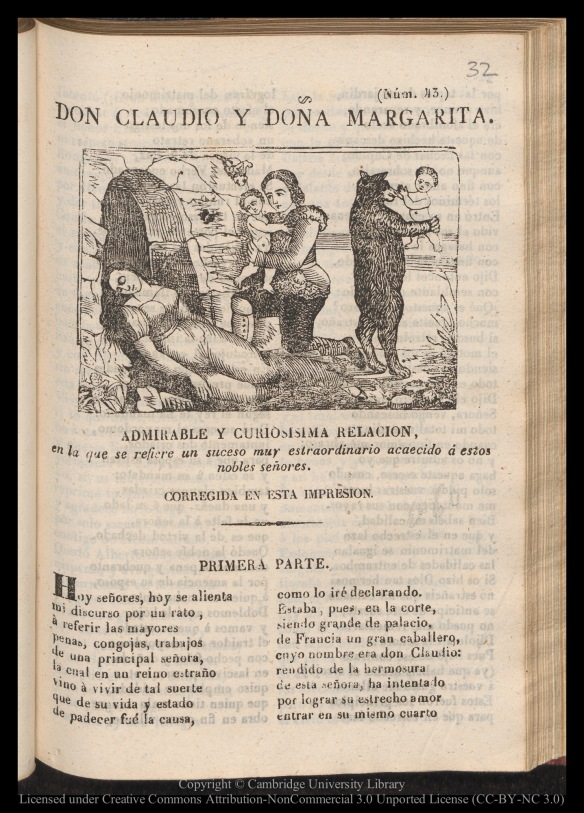

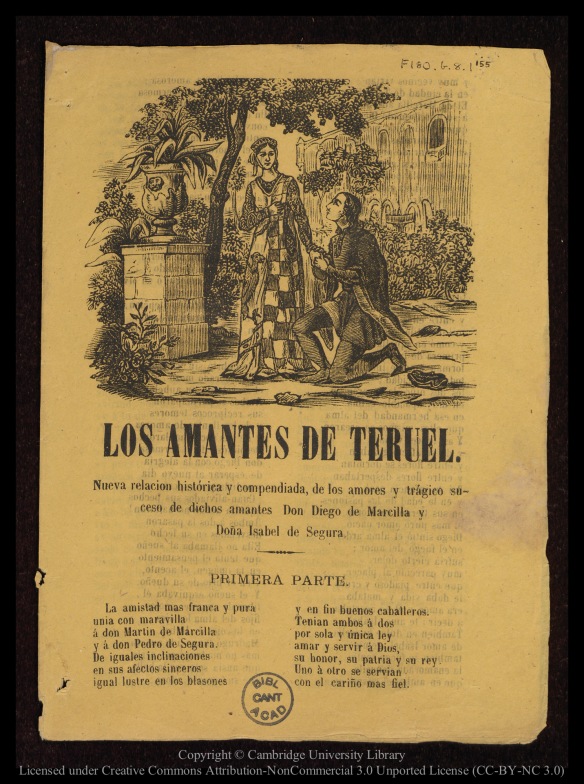

Cambridge University Library was recently awarded a Cambridge Humanities Research Grant to continue work on the Spanish chapbooks catalogued and digitised under the “Wrongdoing in Spain, 1800-1936” project, as featured in the Cambridge Digital Library. This new year-long project aims to reliably date about 67% of chapbooks bearing estimated dates, often drawn from the printer’s period of activity. To establish more accurate dates of printing for these items, we aim to conduct visual search on woodcut illustrations within the chapbooks to compare prints made from the same woodblocks.

Printing houses used woodblocks (as well as metal stereotype plates in the nineteenth century) to illustrate the chapbooks. Woodblocks were expensive to produce, so printers often had a limited stock that they reused, sometimes through several generations of printers. Earlier woodblocks were crudely made on softwood, but the technique developed to produce much more detailed woodblocks etched with metal-engraving tools on harder wood. More intricate images are typical of the later period, although many older woodcuts continued to be used in later years to cut costs. It comes as no surprise then that wood blocks deteriorated over time, becoming less sharp, developing cracks. We see how, after many printings, the finest lines began to fade, and it is this wear-and-tear that we are hoping to use to our advantage to date the Cambridge Digital Library Spanish chapbooks more accurately.

During the first phase of the project (October 2021-to date) images of the chapbooks were run through a machine learning model created by Oxford University’s Visual Geometry Group. The model was pre-trained on similar Scottish chapbooks from the National Library of Scotland. This process recognized the woodcut images and created annotations to mark them using bounding boxes, but the result was not perfect. Manual input was needed to ensure that the gathering of images suited the parameters of the project. Our aim was to isolate individual woodblock prints (i.e., woodcuts made from a single woodblock). The software missed the fact that some images consisting of two or three separate woodblocks had been combined to make an individual image. It also missed borders and garlands and made “false detections”, so manual input was essential not just to serve our purposes for the project, but also to train the machine learning model to make more accurate predictions in the future.

On the next phase of the project, all the images and annotations, alongside metadata from Cambridge Digital Library, will be imported into an instance of VISE (Virtual Geometry Group Image Search Engine). VISE will allow us to visually search many images (we annotated a total of 18,757 images out of 26,527 scanned images of chapbooks). By using an image or a metadata field as a search query, we are hoping to use machine learning and computer vision to explore relationships between the illustrations and not only narrow down the publication dates of the chapbooks, but also open up fields for research in printing and social history.

Sonia Morcillo García

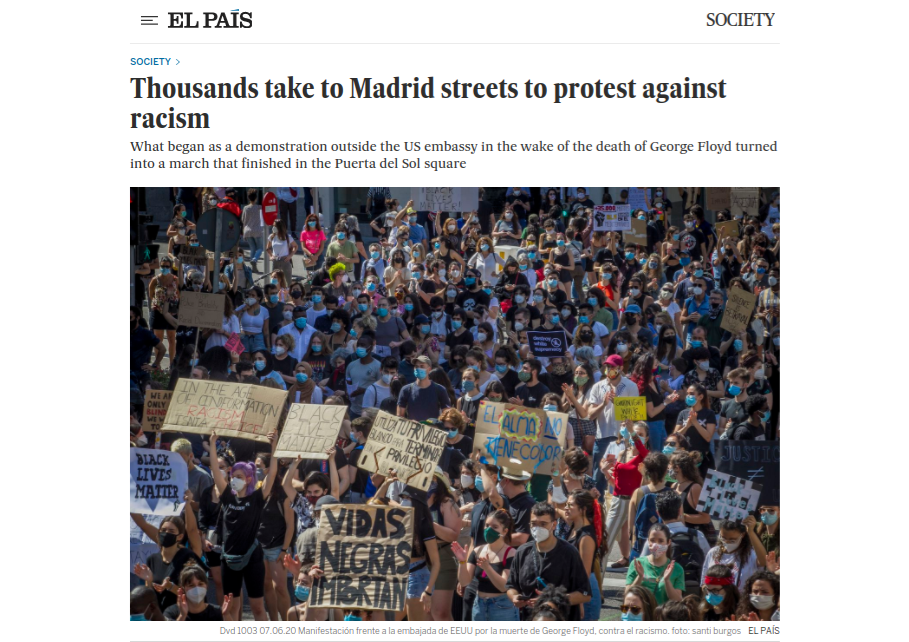

Some resources on racism in Spain and Portugal

In line with recent events linked to the Black Lives Matter movement, this blog post features ebooks and other titles dealing with racism and social prejudice in Spain, Portugal and Portuguese-speaking Africa available to Cambridge students and researchers.

Continue reading “Some resources on racism in Spain and Portugal”

Juan Latino, 16th-century Afro-Spaniard freed slave, poet and Latin professor

Juan Latino (ca. 1517-ca. 1594) was born most likely in Baena (southern Spain), descendent of Guinea born parents. He was the first Afro-European to write in Latin and thus, have a literary career. In fact, he was called “Latino” for his mastery of that language. We should not forget that slavery was common at the time in Europe (see 532:8.b.200.1).

The fascinating story of Juan Latino is for Professor Aurelia Martín Casares (Universidad de Granada) an example of the triumph of wisdom (see C213.c.3056); he was able to break prejudices and social conventions in a somewhat rigid early modern society. In this story the noble family to whom he belonged, played a crucial role in helping make possible his exceptional achievements. Martín Casares compares Latino with the American abolitionist writer and orator Frederick Douglass (who escaped slavery in the 1830s), but makes the point that Latino lived three centuries earlier than Douglass. Continue reading “Juan Latino, 16th-century Afro-Spaniard freed slave, poet and Latin professor”

The Prado Museum, a 200-year story

Last November 19, the museum celebrated the 200 year anniversary of its opening. The University Library regularly receives Spanish art catalogues – including the ones issued by the Prado – but this time we have also acquired a selection of recent books (listed below) commemorating this occasion. Among them we can highlight Museo del Prado, 1819-2019: un lugar de memoria (C202.b.3782), catalogue of an exhibition focused on the museum’s history, organised by the institution. Continue reading “The Prado Museum, a 200-year story”

75 years of Premio Nadal

The Premio Nadal is the oldest literary prize in Spain, awarded by Ediciones Destino (since 1988 part of Planeta group) to the best unpublished novel. We can find many important 20th century Spanish writers among their list of awardees. Four of them have won the Cervantes prize as well (see our post on Premio Cervantes).

The prize is awarded every year on January 6. It was originally the idea of the journalist Ignacio Agustí, editor of the magazine Destino (belonging to the same publishing house) and best known for Mariona Rebull (743:01.d.17.285). The prize was created in order to discover new talent and provide a stimulus for literary creation in the post-war years. It was named after Eugenio Nadal, former editor of Destino, to honour the literature teacher who had then recently passed away at a young age.

The prize is awarded every year on January 6. It was originally the idea of the journalist Ignacio Agustí, editor of the magazine Destino (belonging to the same publishing house) and best known for Mariona Rebull (743:01.d.17.285). The prize was created in order to discover new talent and provide a stimulus for literary creation in the post-war years. It was named after Eugenio Nadal, former editor of Destino, to honour the literature teacher who had then recently passed away at a young age.

The prize was first given in 1944 to Nada (744:35.d.95.359), an existentialist novel by the young Carmen Laforet. Three years later, it was awarded to Miguel Delibes for La sombra del ciprés es alargada (744:35.d.95.300); he is a major figure in Spanish literature of the 20th century, who won the Cervantes prize in 1993. Continue reading “75 years of Premio Nadal”

Sorolla, Spanish master of light

The exhibition Sorolla: Spanish master of light (S950.a.201.6770) that inspired this post is coming to an end at the National Gallery (London) on 7 July, but will open at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin between 10 August and 3 November.

Although probably not known to the English-speaking educated public, Sorolla was the most internationally well-known Spanish artist of his time. A painter with a style close to impressionism, and without any doubt, a master at capturing light.

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863-1923) was born in Valencia, the son of a tradesman, but became an orphan at a young age. Joaquín and his sister were taken under the care of their aunt and uncle, who was a locksmith. Sorolla showed an early interest in painting. He started taking drawing classes in 1874, later followed by studies at the Fine arts school in Valencia. With the support of the photographer Antonio García Peris (see S950.c.201.1204), his future father-in-law, he was able to set up his first studio. Continue reading “Sorolla, Spanish master of light”

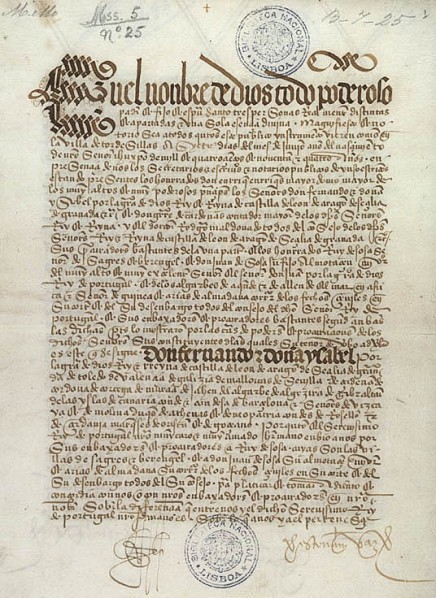

Splitting the world in two: the 525th anniversary of the Treaty of Tordesillas

The 7th June marks the 525th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas. The treaty was named for the Castilian town near Valladolid where it was signed by the Catholic Kings (Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon) and John II, King of Portugal. The signing of this treaty divided those parts of the world newly “discovered” by Spain and Portugal between the empires of the two kingdoms along an imaginary meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands. The lands to the east of this line corresponded to Portugal and those to the west to Spain.

The Treaty of Tordesillas had a precedent, the Treaty of Alcáçovas (1479), that followed the War of Castillan Succession, and already marked the division of the Atlantic into two spheres of influence, one for Spain and the other for Portugal, with the exception of the Canary islands (Spanish, but in the Portuguese sphere). This was confirmed by the papal bull Aeterni regis (Sixtus IV, 1481) which recognised as Portuguese some disputed territories in the Atlantic (Guinea, Madeira, Azores and Cape Verde). More importantly, the treaty recognised Portugal exclusive right of navigation south of the Canary islands. Continue reading “Splitting the world in two: the 525th anniversary of the Treaty of Tordesillas”

Max Aub: a Spanish intellectual in Mexico

Researchers of the life and work of Max Aub (Paris, 1903- Mexico City, 1972) will be pleased to hear about a recent donation from the family of Aub’s daughter María Luísa, affectionately called Mimin by family and friends. Continue reading “Max Aub: a Spanish intellectual in Mexico”