Tag: Spain

Mariano Fortuny y Marsal: a cosmopolitan 19th-century artist

This year marks the 180th anniversary of the birth of Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny 1838-1874 (not to be confused with his son Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo, the fashion designer). For the first time, Madrid’s Museo del Prado held a comprehensive exhibition devoted to Fortuny, showing 169 art pieces loaned by private collectors and major museums including the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya – MNAC (Barcelona) and Museo Fortuny (Venice).

Fortuny was internationally renowned and, after Francisco de Goya (see Glendinning’s donation post), considered one of the best Spanish painters and printmakers of the 19th century. His take on genre painting was fashionable, and collecting his art was a sign of class for the bourgeoisie, as Carlos Reyero explains in his recent book (C205.d.4208). Fortuny had great success painting genre scenes and Moresque-inspired paintings. But at the same time he was an innovator and enjoyed the rare privilege of creating the art he wished. He was very versatile artist; he mastered all the techniques he undertook: oil painting, with precise touch often compared with Ernest Meissonier’s, and especially watercolour and etching, advancing both techniques and achieving new results. He used watercolour in a more modern way, as an autonomous art technique, and not only for preparatory works. His etchings were influenced mainly by the work of Goya, Rembrandt and José de Ribera. As he was more skilful than his contemporaries, he aroused both their envy and admiration. Continue reading “Mariano Fortuny y Marsal: a cosmopolitan 19th-century artist”

The feat of the Real Academia Española’s first dictionary (part 2)

The dictionary lacked a general method and workflows were divided among the authors by combinations of letters. They took for granted that every academic was equally qualified, worked at the same speed, and was following the same criteria as the rest of the team – criteria which, incidentally, were not precisely established from the start. For instance, not all authors were using the same edition of a given work to find the quotes from authorities, so knowing the folio or page number is not particularly useful. The original intentions were too ambitious and some cuts in the plan were required. There was no room for adding the vocabulary of the arts and sciences. This task was postponed, with plans for an eventual separate dictionary dedicated to that vocabulary; a project never undertaken. Continue reading “The feat of the Real Academia Española’s first dictionary (part 2)”

The feat of the Real Academia Española’s first dictionary (part 1)

The Diccionario de la lengua castellana (1726-1739), later known as Diccionario de autoridades, was the first modern Spanish lexicographical work. The Real Academia Española (RAE) was founded in 1713 under the royal auspices and the first generation of academics decided to record the Spanish vocabulary following the example of the language academies in Paris and Florence. They considered that the Spanish language had achieved its zenith in the 17th century, so it was time to preserve it for future generations. This was a huge challenge, considering that the only Spanish precedent, the Tesoro de la lengua castellana, o española (1611) by Sebastián de Covarrubias, one of the first monolingual dictionaries in a vernacular language, was around one hundred years old. They did their job altruistically, “for the honour of serving the Nation”. The founder and first director, Juan Manuel Fernández Pacheco, Marquis of Villena and Duke of Escalona was an inspiring figure and played a major role in the institution. The purpose of the academy was reflected in its motto “Limpia, fija y da esplendor” ([It] cleans, [it] fixes, and [it] gives splendour). Continue reading “The feat of the Real Academia Española’s first dictionary (part 1)”

The Cervantes prize, the most important Spanish literary award

The Premio Miguel de Cervantes is the highest recognition that a Spanish-language writer can achieve. It is an acknowledgement of those whose work has notably enriched Spanish literary heritage. Thus, this prize recognises the career of an outstanding writer. It was created in 1975 in honour of the author of Don Quixote de la Mancha, the most universally known Spanish text and the first modern novel. This literary prize has been awarded annually by the Spanish Ministry of Culture since 1976.

Candidates are proposed by the Real Academia Española (founded in 1713) and all the National Academies of the Spanish language in the different Spanish speaking countries (23 in total). The jury is comprised of literary and academic authorities, in addition to the most recent awardees. Traditionally the prize is given one year to a Spanish author and the following to a Latin American, although this is not a rule. Continue reading “The Cervantes prize, the most important Spanish literary award”

A collection of Spanish broadsides bequeathed by E.M. Wilson

Some 160 Spanish broadsides (known as “aleluyas” in Spanish) have been recently added to the Cambridge Libraries catalogue. They were bequeathed to Cambridge University Library by Edward Meryon Wilson, former professor of Spanish at the University of Cambridge. The collection contains a complete run of one of the longest series of aleluyas ever printed in Spain: the Marés-Minuesa-Hernando series, consisting of 125 numbers. According to Jean-François Botrel [1], the printer Hernando would have acquired this collection from the printers Marés-Minuesa in 1886 and would have started reprinting it shortly afterwards.

These aleluyas can be consulted in the Rare Books Room (classmark F180.bb.8.1). They were printed by Librería Hernando and by Sucesores de Hernando, respectively (the founder and his descendants) between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century (Librería Hernando was founded in 1828; Sucesores de Hernando took over in 1902).

Continue reading “A collection of Spanish broadsides bequeathed by E.M. Wilson”

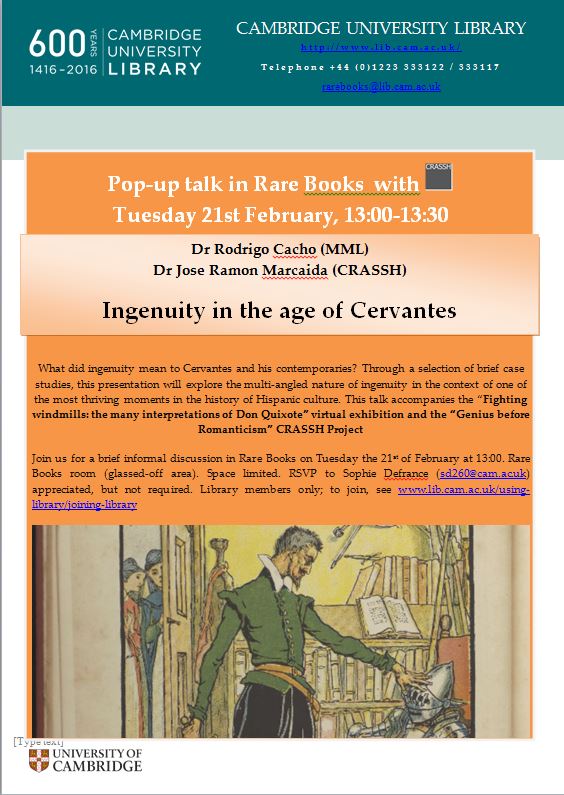

Ingenuity in the age of Cervantes: pop-up talk, Tuesday 21st February

Following the Fighting windmills virtual exhibition, a short in-focus talk will be given on Tuesday 21st February at 1pm entitled Ingenuity in the age of Cervantes. Come and join us for a compelling presentation by Dr Rodrigo Cacho from MML and Dr José Ramón Marcaida from CRASHH (Library members only).

See poster below for more details.

The first polyglot Bible (part 2)

It is very likely, and widely accepted, that Nebrija recommended the printer Arnaldo Guillén de Brocar to Cisneros. Brocar had a good reputation and had exclusive rights to print Nebrija’s works, so he had been printing his books since 1503.

The typography of these volumes is also a great achievement. How to present a complex distribution of the different texts was a problem solved ably by Brocar. He cast new types for several of the alphabets used in the project. The Hebrew and Aramaic types are particularly appreciated; they have, as stated by the incunabulist Julián Martín Abad: “clearly more beautiful designs than those we find in the Iberian Hebraic incunabula”. Brocar cast two different Greek types: one in the Aldine style, and the most remarkable, used in the New Testament; “undoubtedly the finest Greek font ever cut” according to the typographer Robert Proctor. The illustration below shows the distribution of the texts in the first volume. The inner column has the Greek text (Septuagint) with an interlineal Latin translation, the central column has the Latin Vulgate, while the Hebrew text is in the outer column. Continue reading “The first polyglot Bible (part 2)”

The first polyglot Bible (part 1)

The Complutensian Polyglot Bible was the first printed polyglot Bible, and as a result the one that set the model for the following polyglots. 2017 is the 500th anniversary of both the end of the printing process of this Bible and the death of Cardinal Cisneros, promoter and sponsor of the project.

The University of Cambridge has eight complete sets of the Complutensian Polyglot catalogued (four at the UL, two at Trinity College and one each at Corpus Christi and St John’s College libraries). F. J. Norton recorded several more complete or partial copies. He states that one of the UL copies has perhaps the longest history of use in the same library, exceeded only by those in the Vatican and Colombina (Seville) Libraries. It was presented by Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall (1474-1559) when he was still bishop of London; that is to say, no later than February 1530 (see inscription on t.p.). Continue reading “The first polyglot Bible (part 1)”

Fighting windmills – new virtual exhibition on Don Quixote at the University Library