The Complutensian Polyglot Bible was the first printed polyglot Bible, and as a result the one that set the model for the following polyglots. 2017 is the 500th anniversary of both the end of the printing process of this Bible and the death of Cardinal Cisneros, promoter and sponsor of the project.

The University of Cambridge has eight complete sets of the Complutensian Polyglot catalogued (four at the UL, two at Trinity College and one each at Corpus Christi and St John’s College libraries). F. J. Norton recorded several more complete or partial copies. He states that one of the UL copies has perhaps the longest history of use in the same library, exceeded only by those in the Vatican and Colombina (Seville) Libraries. It was presented by Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall (1474-1559) when he was still bishop of London; that is to say, no later than February 1530 (see inscription on t.p.).

The best European academics had been waiting for such a major intellectual project: a Bible which gathered simultaneously the entire text in their original languages (Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek) and the Latin translation free from later corruptions. Francisco Jiménez (or Ximénez) de Cisneros (1436-1517), religious figure and statesman (twice regent of Castile) took up the challenge, and his leadership was crucial to accomplish the project. This happened before the start of the Reformation in 1517, when the first polyglot Bible had been printed but not distributed.

Cardinal Cisneros was determined to reform the Catholic Church in Spain. As he was Archbishop of Toledo, the main archdiocese of Spain, he could commission this costly project. He founded the Complutensian University (Complutensian Universitas) in Alcalá de Henares (near Madrid) for the purpose of developing theological studies. As Alcalá was a fruitful academic centre for Christian humanism, it was soon praised by important authorities like Erasmus. According to Álvar Gómez de Castro, Francis I, King of France, showed his admiration to Cisneros saying: “A single friar has done in Spain what in France would have taken many kings.”

It was not by coincidence that this happened in Spain; the cultural context was propitious for it. Historically the Jewish community had been important in the country. They developed distinguished rabbinical schools producing translations directly from Hebrew. But after the Jews were expelled in 1492, only the ones that embraced Christianity were allowed to stay. A few of these conversos (converts) were the pillars of Cisneros’ great editorial achievement. And, after all, some important Jewish collections remained available in Spain.

The Complutensian enterprise was regarded as suspicious by some sectors of the Church because it could promote heresy: since they were printing the Bible in Hebrew, with the Aramaic version of the Vulgate corrected. Moreover, converts played a fundamental role in the project.

Completing such a project required a highly capable team of experts in ancient languages. Diego López de Zúñiga, Demetrios Doukas of Crete and Hernán Núñez de Guzmán (known as el Pinciano) were in charge of the revision of the Greek texts; the Hebraic text was handled by three converted scholars: Alfonso de Alcalá, Pablo Coronel and Alfonso de Zamora. In addition, the eminent Professor Antonio de Nebrija was also involved to some extent in the project. He was the best possible editor of the Latin texts.

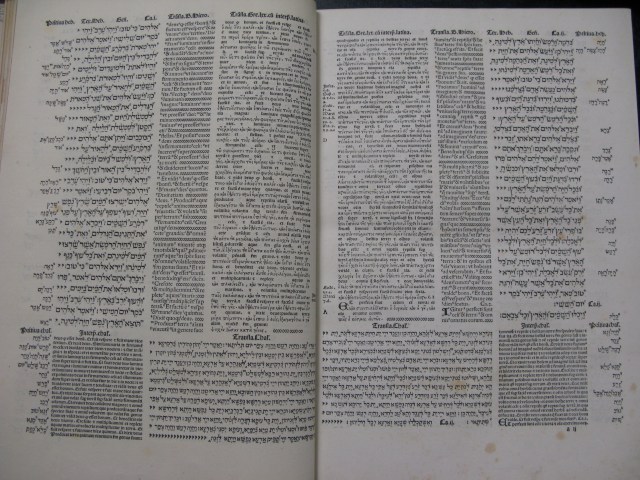

The project also pioneered modern biblical textual criticism and a scientific approach to the subject by hiring language experts required for that task. This Bible gathered for the first time the different Scriptures in their original versions, so they could be compared and contrasted directly. It was necessary to correct the Old Testament according to the Hebrew text and the New Testament according to the Greek text. Cisneros’ Bible includes all these revised texts: the Latin Vulgate, the Greek Septuagint, the Aramaic Targum Onkelos, including Latin translations of the last two. As a result, it was necessary to find the best biblical sources.

Cisneros paid the expenses involved in copying the manuscripts for his team of scholars; furthermore two Greek O.T. manuscripts from the Vatican Library were taken on loan with the Pope’s acquiescence, and a copy of a Greek O.T. codex was sent from the Senate of Venice. Other primary sources were available in the country, especially in Madrid and in the King’s library at El Escorial monastery.

[Go to part 2]

Manuel del Campo