One of the last books acquired through the Liberation collection is Amy Bakaloff’s Sombre est noir (Liberation.b.356), a collection of French poetry written during the Second World War and dedicated to Paul Éluard and Georges Hugnet, a writer and publisher engaged in the Résistance. It includes an engraving signed by Óscar Domínguez and two drawings. It is a rare work, one of 232 copies, some numbered on Annam paper, some on blue vellum, and some on vélin des Marais.

An interesting feature of this publication is, as indicated by the colophon, the reprint of poems already published in an anthology by Les Editions de Minuit in 1944: L’Honneur des Poètes (II, Europe, Liberation.c.840) and in the literary journal L’éternelle revue, both directed by Éluard.

Les Editions de Minuit, founded in 1941 by the engraver Jean Bruller and the writer Pierre de Lescure, were launched with Le Silence de la mer (Liberation.c.830) by Vercors (the literary pseudonym of Bruller). During the Occupation, they published clandestinely writers of Résistance, against the censorship and propaganda of the Vichy régime.

L’Honneur des Poètes, II, Europe, Paris: Éditions de minuit, 1944. Liberation.c.840

L’Eternelle revue, whose first two issues were published clandestinely, was founded by Paul Éluard, and published by the Editions de la Jeune Parque (named after a poem of Paul Valéry published in 1917) between June 1944 and November 1945. The journal was edited by Louis Parrot, a writer and literary critic close to Éluard, who also contributed to the collection L’honneur des poètes (I) (Liberation.c.832). Parrot published at the end of 1945 L’intelligence en guerre (Liberation.c.957), a work on the intellectual and artistic resistance under the Occupation. The Cambridge University Library copy of Bakaloff’s Sombre est noir (Liberation.b.356) is dedicated by the author to Louis Parrot and refers to the liberation of Paris in August 1944.

Relatively forgotten, the poet, Amy Bakaloff Courvoisier (1907-1984), born to a French mother and a Bulgarian father (a Communist exiled to the USSR and then to Paris), was a student during the inter-war period. He joined a circle of artists and writers linked to the surrealist movement (Victor Brauner, André Breton, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dali, Robert Desnos, Paul Éluard, Georges Hugnet, Angel Hurtado, Wifredo Lam, Pablo Picasso, Paul Valéry, Oswaldo Vigas…), which is probably how he met Óscar Domínguez. Under the Occupation, Amy Bakaloff took the pseudonym of Jean Jaquet and was involved in various resistance actions: anti-German communications and propaganda, production of fake identity cards, etc. In 1943, Bakaloff joined the “Pavillon noir” Résistance network as an interpreter, to help fugitive Russian allies and provide strategic intelligence on the situation in Normandy.

His poems in Sombre est noir invoke departure, action, struggle, violence, destruction and commemoration. They feature snapshot images, oscillating between objective descriptions in the third person (“L’hôtel Continental est dans la rue Castiglione / L’hôtel Continental est un cimetière” p. 13) and the use of a collective voice (“Nous sommes là nous sommes tous là / Partout dans ce Paris enflammé… Nous sommes là / Nous guettons…” p. 31). The enemy is mentioned at times in the singular, others in the plural:

His poems in Sombre est noir invoke departure, action, struggle, violence, destruction and commemoration. They feature snapshot images, oscillating between objective descriptions in the third person (“L’hôtel Continental est dans la rue Castiglione / L’hôtel Continental est un cimetière” p. 13) and the use of a collective voice (“Nous sommes là nous sommes tous là / Partout dans ce Paris enflammé… Nous sommes là / Nous guettons…” p. 31). The enemy is mentioned at times in the singular, others in the plural:

L’ennemi se cache

L’ennemi se sauve

L’ennemi se perd

L’ennemi nous tue

Et disparaît (p. 33)

The “je”, which appears surreptitiously in the poem XIII “Plaine ma plaine”, p. 49-50, emerges in the final stanza of the last poem, XIV:

La honte efface-t-elle les désirs

Les serres réchaufferont-elles l’espoir

Je crois Je marche Un but Désir

J’espère (p. 55).

The illustrations of Óscar Domínguez (1906-1958) for Sombre est noir were produced at a later stage. The etching and the drawings do not maintain a strictly illustrative relation to Bakaloff’s text. Domínguez was a Spanish painter who moved to Paris in the late 1930s. Before the Second World War, he contributed to several publications of Guy Lévis Mano and in many surrealist books and exhibitions. Domínguez participated in numbers 12-13 of the surrealist magazine Le Minotaure published by Albert Skira and directed by André Breton and Pierre Mabille (1933-39). In 1938, Domínguez contributed to the International Surrealist Exhibition organised by Breton and Éluard at the Galerie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In 1939, he went to Marseille, where he attended André Breton’s circle (Ernst, Péret, Marcel Duchamp, Hans Bellmer, Wilfredo Lam, André Masson, René Char…).

He returned to Paris in 1941, mixing with Hugnet, Lucien Coutaud, André Thirion and Apel·les Fenosa, as well as Éluard and Picasso, and participated in the surrealist collective “La Main à plume” (1941-44). He also took part in the 1940 International Surrealist Exhibition at the Art Gallery of Mexico. His activity as an illustrator and a painter continued under the Occupation and after the war. Domínguez illustrated the 1947 edition of Éluard’s Poésie et vérité 1942 published by Les Nourritures terrestres.

The question of darkness is at the heart of his initial etching for Sombre est noir (see first image) which shows a female figure with long hair dressed in a loose garment, sliding from right to left, descending a staircase and holding a candle in her hand. This illuminates the left part of the image, while the rest of the space is darkened by concentric lines evoking imprisonment through rolls of barbed wire.

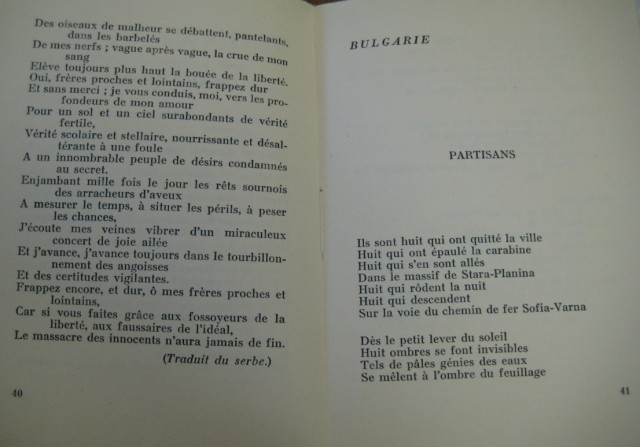

The lithographic design inserted between poems III and IV of the collection (above) depicts two human figures. A female figure is standing up, her arms raised, her mouth open and her tongue drawn, as if to shout her anger or pain at the destruction and fire featured in the background. Another person is kneeling in front of her, hugging her, head down, eyes closed, tongue hanging out, expressing not indignation and revolt, but rather exhaustion, or even death; sadness and the search for comfort.

Poems III and IV do not feature people: poem III, which echoes the title of the collection, constitutes a meditation on darkness, night and day, showing a glimmer of hope on the horizon. The poem uses rhymes, something unusual in the rest of the collection where the lyrical form subsists in the use of stanzas and refrains.

The play between darkness and light is more striking in the initial engraving of Domínguez than in the drawing following immediately the poem. The drawing maybe echoes poem IV, rhythmed by the refrain “Cette nuit”, and forming a sequence of dramatic scenes, natural and human disasters, from the howling of wolves to the bloody silence of accomplices: “Cette nuit / La haine recouvre de sang le silence de ceux qui se sont tus” p. 21.

In the drawings of Domínguez, in dialogue with each other, the black line on the white paper creates degrees of light and darkness. The two drawings are variations of the same through the repetition of the same composition. The pattern of black intertwined lines on the dress of the woman in the second drawing echoes the depiction of obscurity in the etching, while the destructive fires represented in the drawings find a new and more positive form in the flame of the candle held in the initial image. In Sombre est noir, the succession of poems oscillating between the narrative and the lyrics unfolds the trauma of the war, the experience of the Occupation and the acts of resistance.

After a first publication of some of his poems in anthologies published during the war, Bakaloff had in 1945 the opportunity to reclaim what had been published clandestinely at the Editions de Minuit and was reprinted in the series entitled “Sous l’oppression”, in a collection of war poems from different European countries. In those publications, the poems were presented as translated from Bulgarian and under the titles “Partisans” and “Section d’assaut”, maybe suggested by the editor, which do not feature in the 1945 edition.

Even the poetry volume is only a “plaquette”, the 1945 publication allowed Bakaloff to present his work as a coherent, single-authored poetic collection. Domínguez’s images appropriate this poetic frame by depicting female figures with sharp outlines, screaming and exhausted, or hopeful and pacified, in their confrontation with darkness and light, death and fire.

Irène Fabry-Tehranchi

Further reading:

Bakaloff Amy, Sombre est noir, orné d’une gravure à l’eau-forte et de deux dessins de Domínguez. Paris, 1945. Liberation.b.356

Sylvie Merigoux, « Mon ami Amy, le poète voyageur qui adorait le cinéma… », Ruth Bessoudo, les pérégrinations d’une artiste voyageuse, blog post, 19/02/2019.

Carreño Corbella, P. Óscar Domínguez en tres dimensiones: catálogo razonado de obras, Gobierno de Canarias, 2010.

Debû-Bridel, Jacques, Les éditions de minuit: historique. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1945. Liberation.c.1602

Benjamin Péret, Le déshonneur des poètes, Mexico: Poésie et révolution, 1945. Liberation.c.108

Exodo hacia el sur: Óscar Domínguez y el automatismo absoluto 1938-1942. Madrid, Ediciones del Umbral, 2006.

L’honneur des poètes, Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1943. Liberation.c.832

L’Honneur des Poètes, II, Europe, Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1944. Liberation.c.840

Musée Cantini, La Part du jeu et du rêve: Óscar Domínguez et le surréalisme, 1906-1957, Marseille et Paris, Hazan, 2005. S950.a.200.380

Parrot, Louis, L’intelligence en guerre: panorama de la pensée française dans la clandestinité. Paris: La Jeune Parque, 1945. Liberation.c.957

Simonin, Anne, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1942-1955: le devoir d’insoumission. Paris: IMEC, 1994. 850.c.549

Vercors, La bataille du silence: souvenirs de minuit. Paris: Presses de la Cité, 1967. 738:45.c.95.451

The material of this blog is part of a paper presented at the conference L’édition de création 1930-1970. Le grand illustré, et après ? organised by Sophie Lesiewicz (Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet) & Anne-Christine Royère (Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne) at the BnF-Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Paris, 3 June 2019.