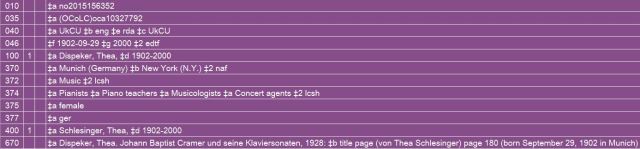

One important aspect of the cataloguing we do in European Collections is authority work. For every book that we catalogue, we check against the United States Library of Congress Name Authority File to make sure that the names of authors or subjects are “authorised”. This is a way to ensure that different people who share the same name can be uniquely identified, and often results in dates of birth and/or death, middle names or initials, titles such as Dr. or words describing their occupation e.g. “historian” being added to a name in our catalogue to help us identify the correct person. Having people uniquely identified in our indexes allows us to group together books by or about the same person.

Whenever we come across a name for which there is no authorised heading in the Name Authority File, we fill in a form with all the relevant information that we have found. The senior members of staff in our department then use this to submit a new authority record to the NACO Program (Name Authority Cooperative Program), a project of the PCC (Program for Cooperative Cataloguing) based at the Library of Congress. Cambridge University Library is an active member of the NACO program alongside over 800 other institutions. During the year to September 2015 we were one of only eight member institutions to contribute over 5000 new name authority records, a figure of which we are very proud.

A little research is often required to establish who it is we are dealing with, particularly when the information in the book itself is minimal. In the course of this research we sometimes uncover more about a person than we strictly need but it is interesting to read about the lives of these people and to flesh out their story; the rest of this post is devoted to three recent examples:

Thea Dispeker (1902-2000) first came to my attention when I was cataloguing a copy of her doctoral thesis from 1928, entitled Johann Baptist Cramer und seine Klaviersonaten (MRC.405.90.1) which she worked on at Munich University. At that time she was called Thea Schlesinger, a name which had no authorized heading in our names index so I knew that I needed to do an authority proposal. On looking up the name in VIAF (Virtual International Authority File, an online resource hosted by OCLC that we use) I found a cross-reference to the name Thea Dispeker which was already in use by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. A quick Google search of this name led me to a New York Times obituary from July 2000, published shortly after her death at the age of 97 and revealing that she had had a most remarkable life:

- At the age of 12 she briefly ran away with a travelling circus (unsurprisingly, she does not mention this in the CV at the back of her thesis!)

- Aged 22 she visited Egypt, viewed Tutankhamun’s tomb and contracted polio from which she recovered

- She was briefly married to a man called Dispeker but the marriage ended in divorce after only months

- In 1938 she escaped from Nazi Germany (her thesis CV stated that she was “israelitischer Konfession” i.e. Jewish) and travelled to the United States (her family had joint citizenship because her grandfather had emigrated to the States in the 19th century and her father had been born there)

She settled in New York and initially taught piano to make a living. She then joined the W. Colston Leigh Bureau, a speakers’ agency, where she set up a classical music section, representing opera stars. This work was the precursor for her setting up her own classical music artists agency in 1947, a company still flourishing today. She represented many famous musical names; among them was the cellist Pablo Casals and in 1950 she helped him to organize the first Pablo Casals festival in Prades, France, his adopted town. She continued to work in her agency until she reluctantly passed over control to her successor in 1998 when she was 96. The New York Times obituary describes her as “erudite, opinionated, acerbic” and also tells how she continued to drive into very old age, with employees dreading being offered a lift by her as the experience was so terrifying.

(Extra biographical information was obtained from Hamburg University’s online Lexikon verfolgter Musiker und Musikerinnen der NS-Zeit and a New York Times article from April 1997 published on the 50th anniversary of her agency.)

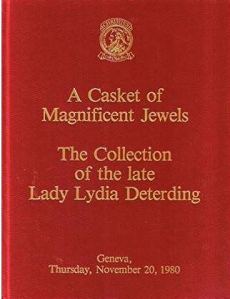

While completing the cataloguing of a Special Collection on gemstones donated by Michael O’Donoghue we had numerous auction catalogues to deal with. Two in particular caught my attention as the owners of the jewels being sold needed their names to be authorised and in researching them I discovered that both were Russian emigrés. Here are brief biographies of them based upon information found online, some of which is rather vague and uncorroborated:

Lydia Deterding (1896/1904?-1980) was born Lydia Pavlovna Koudoyaroff in Tashkent. Her father was a Tsarist general and at the age of 16 she married General Bagratouni. She presumably left Russia at the time of the Revolution and by 1924 she was in Paris where she married the then 58-year old Sir Henri Deterding, chairman of the Royal Dutch Shell oil company. There is a suggestion that she had previously been the mistress of Calouste Gulbenkian, also in the oil business and a rival of Deterding. She had two daughters with Deterding but they divorced in 1936. During the 1920s and 1930s she helped Russian emigrés and was recognised for this in 1937, being granted the title Princess Donskaya (the highest title that can be conferred on non-royal Russians) by Grand Duke Cyril, cousin of Tsar Nicholas II. In Jet set: a memoir of an international playboy (1999), Massimo Gargia wrote about a romance with her when she was 80 and claimed that she had told him stories of the sexual inadequacies of her ex-lover Adolf Hitler!

Among the jewellery of Lady Lydia Deterding sold by Christie’s in Geneva in 1980 was the Polar Star diamond, which had previously belonged to Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte and the wealthy Russian family, the Yusupovs. Prince Felix Yusupov, who was implicated in the death of Rasputin, sold the diamond to Cartier from which the Deterdings bought it. Another item in the sale was a diamond and pearl necklace which had belonged to Empress Maria Feodorovna, mother of Nicholas II.

Vera Hue-Williams (1899-1992), the daughter of a barrister, fled Russia in 1917 with her mother, Baroness Kostovsky, and sister Olga, apparently penniless apart from the jewels sewn into her petticoat hem. Like many leaving Russia they ended up in Paris where in 1927 she married her first husband, a British diplomat called George Owen. This marriage ended in divorce and in 1931 she became the second wife of Walter Sherwin Cottingham of the Berger Paint company (his first wife had been the soprano, Maggie Teyte). After Walter’s death in 1936 Vera married again in 1940, this time to Thomas Lilley, chairman of the shoe firm Lilley and Skinner. Together they founded the Woolton House Stud near Newbury and also lived at Middleton-on-Sea near Goodwood where they entertained lavishly. Thomas Lilley died in 1959, and in 1963 Vera married her fourth husband, Colonel Roger Hue-Williams. She continued to breed racehorses including her husband’s horse Altesse Royale which won three major races in 1971. Roger predeceased her in 1987 and when she died in 1992 she left £9 million. The sale of her jewels raised around £3 million.

Katharine Dicks

Fascinating … makes our lives seem very humdrum!

vera was a greater person than her inheritors… unfortunately and the official ‘money’ was probably less than actual money gained… there was some fiddling happening after her death… they wouldn’t even pay a grand to retire altesse for the remainder of life