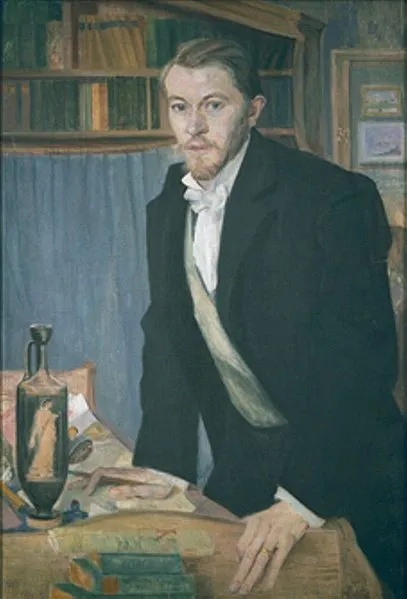

One hundred years ago, on March 25, 1921, the influential art patron Karl Ernst Osthaus died. His name may not be very well-known but he was a key player in establishing Modernism in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century, being active as an art patron, founding a museum and being involved in the Werkbund.

Osthaus was born in 1874 into a wealthy family and grew up in the industrial town of Hagen in Westphalia. And it was in Hagen that he tried to realize many of his later projects.

During his studies of art history and philosophy he encountered the ideas that art plays an important part in improving the lives of all social classes. A large inheritance gave him the means to attempt to put these ideas into practice. First, he commissioned a museum to be built in Hagen to house his large art collection and make it accessible to the public. While the museum was being built, he came across the work of the architect Henry van de Velde and was so impressed that he commissioned him to design the interior of the museum. In 1902 the museum opened as the Folkwang Museum. It is now regarded as the first museum building specifically designed to house modern art. After Osthaus’ death his collection was moved to nearby Essen but the museum building was subsequently restored and is now known as the Osthaus Museum.

Osthaus continued to work with van de Velde for the design of his residence in Hagen, Hohenhof, an excellent example of Art nouveau architecture. Osthaus’ appreciation of van de Velde is demonstrated in his monograph on him published in 1920, one of the first full-length studies of van de Velde’s life and work. The University Library holds a facsimile edition of this work (S401:7.b.9.793) and a digital copy of the original edition is available via the German National Library.

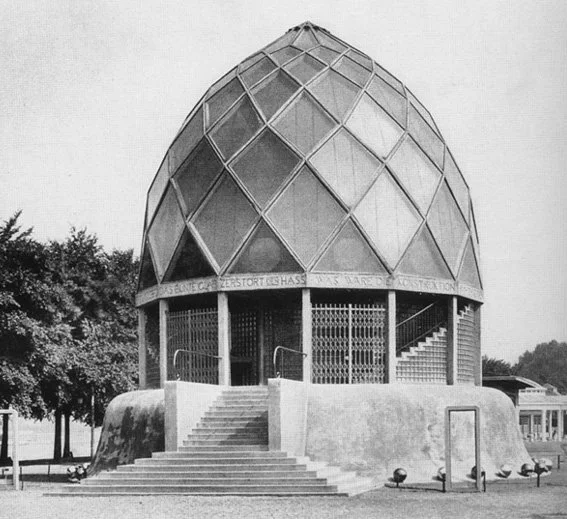

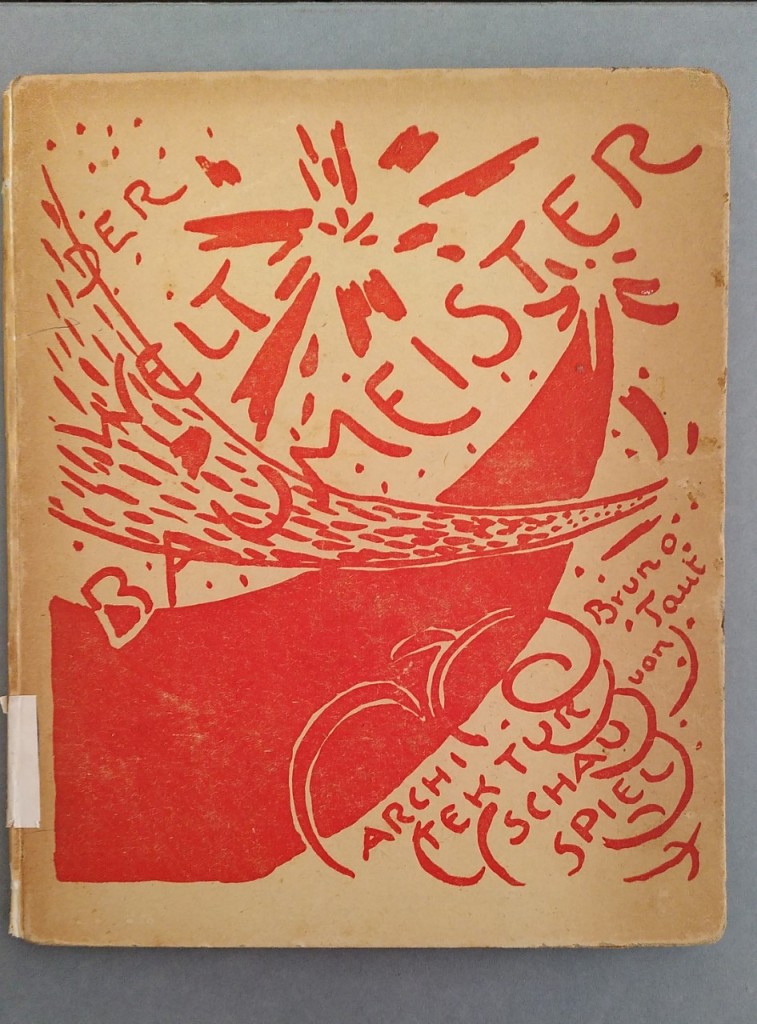

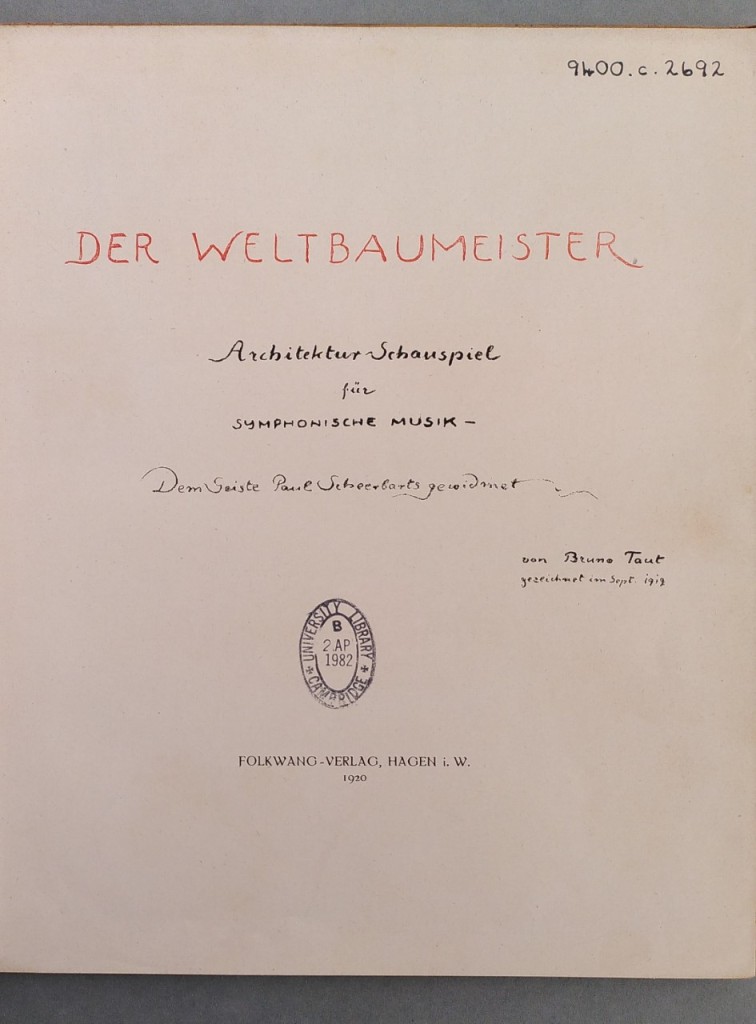

Karl Ernst Osthaus was an active member of the Werkbund, the organisation founded to promote useful design by combining the applied arts with modern technology. He was instrumental in organising the first Werkbund exhibition held in 1914 in Cologne where the architect Bruno Taut showed his famous Glass Pavilion. Osthaus engaged Taut for his plans in Hagen, hoping to build a central civic building (Stadtkrone) according to Taut’s ideas. While these plans were not realised, a fascinating work published in 1920 by the Folkwang Verlag founded by Osthaus allows us to get an idea of Taut’s visionary architecture. Der Weltbaumeister: Architektur-Schauspiel für symphonische Musik, dem Geiste Paul Scheerbarts gewidmet consists of Taut’s drawings for an ‘architectural play’. The University Library is lucky to hold a copy of this delightful work (9400.c.2692).

While some projects for Hagen were achieved, such as the workers’ housing development designed by Richard Riemerschmid and villas designed by Behrens, many were not mainly due the outbreak of World War I. Osthaus served in the war but became severely ill. He never fully recovered and died at the age of 47.

Sadly, no comprehensive biography of Karl Ernst Osthaus has been written yet but several publications document his activities and influence.

Most useful is probably the collection of his speeches and writings published in 2002: Reden und Schriften. Folkwang – Werkbund – Arbeitsrat (401:1.b.200.11).

The collaboration between Osthaus and Taut is investigated in the monograph entitled: Auf dem Weg zu einer handgreiflichen Utopie: die Folkwang-Projekte von Bruno Taut und Karl Ernst Osthaus (401:7.c.95.591).

And most recently the library acquired the volume of the correspondence between Osthaus and Walter Gropius (S950.b.201.6559) which allows us to reconstruct how supportive Osthaus was of Gropius’ Bauhaus ideas.

It would be good to think that the anniversary of his death might stimulate further research into the life and work of Karl Ernst Osthaus and that eventually a full biography could be written and published.

Christian Staufenbiel