Dr Dan Knorr of the Faculty of History explains the significance of a huge new Chinese acquisition.

It is no secret that the study of China, especially in the premodern period, is heavily conditioned by the availability of source material. Both the opening of archives and the digitization of archival materials have opened up exciting new avenues for research in recent decades. However, concerns about both physical and digital access to these materials temper optimism about this trend stretching endlessly into the future. Moreover, the uneven regional and chronological distribution of historical materials available to and appreciated by scholars continues to impose limits on our understanding of China.

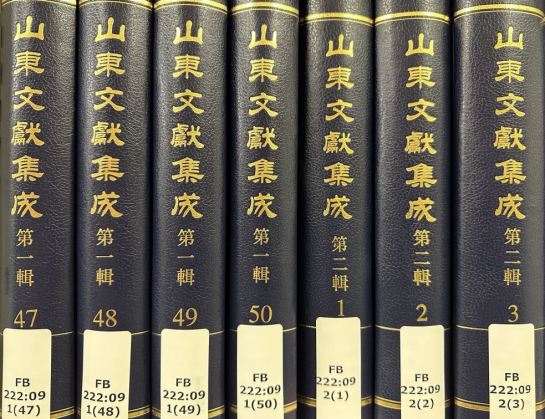

Against this backdrop, the University Library’s recent acquisition of the 200-volume collection Shandong wen xian ji cheng 山东文献集成 offers exciting opportunities for scholars of China across the premodern and modern periods.

This printed collection comprises black-and-white photographic reproductions of more than 1,000 individual texts held at 15 institutions (mostly in Shandong), including the Shandong Provincial Library, the Shandong Provincial Museum, Shandong University Library, and the Jinan Municipal Library. The largest portion of the collection consists of texts from the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), but works from as early as the Han (202 BCE–220 CE) to as late as the Republican period (1912–1949) are also included. The topics covered vary just as widely: from philosophy to philology to literature to politics. The authors represented almost all hail from Shandong itself and range from the world-famous to the obscure. The table of contents helpfully includes information about authors’ home places, making it feasible to identify texts most likely to be relevant to one or another place within Shandong.

Shandong wen xian ji cheng is thus an invaluable tool for either researching Chinese history generally or the local history of Shandong and places within it. Shandong is undoubtedly an important province, housing the ancestral homes of great sages like Confucius and Mencius and the sacred peak of Mt. Tai. In the Qing period, it produced famous figures like the scholar-official Wang Shizhen, who played a crucial role in the consolidation of Qing rule, and the world-famous author of ghost stories, Pu Songling. Nevertheless, the study of Shandong’s regional history, especially in the English language, has lagged behind that of other parts of China. For example, the rich source base available to scholars studying the economically and culturally vibrant Lower Yangzi region has made it an especially attractive object of study. Likewise, the uniquely well-preserved county archives of Ba xian (Chongqing), have made it the go-to location for researchers interested in local administration and legal history. In comparison, Shandong has been somewhat lost in the shuffle. However, the ready availability of such a wide range of sources in Shandong wen xian ji cheng demonstrates that this need not be the case.

While it would be impossible to comprehensively summarize the potential value of this collection, a couple examples from my own research indicate its broad utility. In volume 3-42 (the collection consists of 4 series, each comprising 50 volumes) we find a collection of writings by six members of the Zhu family who came from Licheng County (Jinan). Although not widely known, the Zhu’s were an extraordinarily powerful family in the early Qing, with two members of the family rising to hold high-ranking positions as provincial officials. The family experienced a steady decline from these political heights, but they remained fixtures in local society and culture. As a youth, Zhu Xiang 朱缃 (1670–1707), who produced five volumes (juan 卷) of poetry included in this collection, was tutored by Wang Shizhen, later gained renown as a poet himself (despite not holding an official position), and bonded with the aforementioned Pu Songling over their shared love for stories of ghosts and strange happenings. Zhu likely contributed material to several stories that appear in Pu’s magnum opus Liaozhai zhiyi 聊斋志异, and his family preserved one of the early manuscript versions of this text. The presence of poetry by Zhu Xiang and other members of the family in Shandong wen xian ji cheng thus offers insight into the local and familial history of the early decades of Qing rule and major milestones in the cultural history of China.

A very different set of materials appears in volume 3-17 in the form of a record of proceedings of the Shandong Provincial Assembly from its 1910 session. At this point in time, Shandong’s provincial assembly was controlled by a conservative faction that resisted efforts by revolutionary military officers to swing the province against the Qing in 1911. However, these records indicate that despite what their conservative reputation and loyalist credentials might lead us to assume, Shandong’s assembly members forcefully agitated for the advancement of local self-government and constitutional government in the lead-up to the 1911 Revolution. Whereas most studies of the 1911 Revolution understandably focus on elites who sided with the revolution, these records from Jinan offer an enlightening perspective on the activities of anti-revolutionary elites who nevertheless genuinely shared their peers’ commitment to political reform.

Brief though they are, these two examples illustrate the wide range of materials included in Shandong wen xian ji cheng, their value for conducting research on local history, and the potential importance of research on this part of China for gaining a deeper understanding of major historical developments. Records on Worldcat indicate that the University Library is now one of only two libraries outside China (the other being Stanford) to own this collection. Having conducted research at some of the libraries that hold the original materials included in Shandong wen xian ji cheng, I can say that they are (or at least were) by no means closed to outside researchers. However, they can be difficult to access, and reproduction privileges can be tricky to negotiate. Hence, it is a tremendous boon to be able to access this published collection in Cambridge. Beyond the value of the material included therein, it is to be hoped that Shandong wen xian ji cheng will also spur readers’ interest in the numerous rare manuscripts held by these libraries not included in the collection and thus become a springboard to even deeper research into diverse facets of Shandong’s history.

Classmarks and links to iDiscover records:

山東文獻集成. 第 1 輯 (Shandong wen xian ji cheng di 1 ji): FB.222:09.1(1)-(50)

山東文獻集成. 第 2 輯 (Shandong wen xian ji cheng di 2 ji): FB.222:09.2(1)-(50)

山東文獻集成. 第 3 輯 (Shandong wen xian ji cheng di 3 ji): FB.222:09.3(1)-(50)

山東文獻集成. 第 4 輯 (Shandong wen xian ji cheng di 4 ji): FB.222:09.4(1)-(50)

山東文獻集成總目圖錄 (Shandong wen xian ji cheng zong mu tu lu): FB.222:09.5

If you need help to locate the materials, please contact the Chinese Section at Chinese@lib.cam.ac.uk