This blog post revisits, as promised earlier, the theme of new additions to the UNESCO World Heritage list, concentrating this time on spa towns. Eleven towns in seven different countries formed a collective transnational nomination that was successful in July 2021. The towns are:

- Baden bei Wien (Austria)

- Spa (Belgium)

- Františkovy Lázně, Karlovy Vary and Mariánské Lázně (Czechia)

- Vichy (France)

- Bad Ems, Baden-Baden and Bad Kissingen (Germany)

- Montecatini Terme (Italy)

- Bath (United Kingdom)

United by the healing properties of their waters, these resorts were chosen to represent spa culture which had its heyday from the 18th century to early in the 20th century. Now, in the cold of winter after a period of possible festive overindulgence, is the perfect time to envelop ourselves with thoughts of such places with their thermal springs and health cures. Using, as ever, resources held in the University Library, I will look back to a time when these were fashionable leisure destinations, frequented by famous visitors and stimulating the publication of many guides and handbooks.

Many spa towns experienced huge growth in visitor numbers as they moved from being the domain of elite aristocrats in the 18th century to being popular with many from the middle-class bourgeoisie in the 19th century, doubtless aided by the coming of the railway. Vichy was no exception to this but its mineral springs had been known about long before, even by the Romans. Madame de Sévigné, the French aristocrat famous for her letters, visited in 1676 and wrote vividly of her drinking and bathing cures, accepting that they did her good (“Je me suis assez bien trouvée de mes eaux, j’en ai bu douze verres”) whilst finding the taste unpleasant and the showers shockingly scalding. Nevertheless she returned the following year.

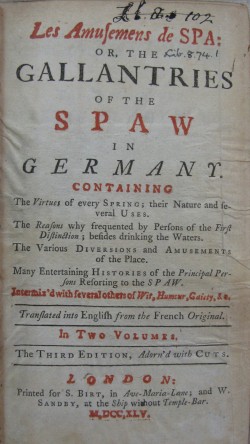

The growing popularity of the mineral springs of Spa were already in evidence in 1745 when the translation of Les amusemens de Spa (Lib.8.74.1-2) was published. From the 1750s onwards lists of visitors were published; the UL has an example from 1777, Liste des seigneurs et dames, venus aux minerales de Spa l’an 1777 (7000.c.323(10)). This makes for interesting reading. During the season, which ran from June to October, the total number reached over one thousand. A good number of the town’s visitors were English.

Click on each image to see larger version

Bad Kissingen was the spa chosen by Mary Shelley in the 1840s and she wrote about her time there in Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842, and 1843 (O.16.3-4), being particularly unimpressed by the food:

We dine at one at the table d’hôte of the Kurhaus; the ceremony is, to the last degree, unsatisfactory and disgusting. The King of Bavaria is so afraid that his medicinal waters may fall into disrepute if the drinkers should eat what disagrees with them, that we only eat what he, in conjunction with a triumvirate of doctors, is pleased to allow us. Every now and then a new article is struck out from our bill of fare, notice being sent from this council, which is stuck up for our benefit at the door of the salle-à-manger, to the effect that, whoever in Kissingen should serve at any table pork, veal, salad, fruit, &c. &c. &c., should be fined so many florins. Our pleasures of the palate are thus circumscribed, not to say annihilated; for the food they give us is so uninviting, that we only take enough barely to sustain life: for, strangely enough, though butter is prohibited, their dishes overflow with grease.

We learn from Ian Bradley’s Water music: music making in the spas of Europe and North America that Mozart composed his short motet Ave verum corpus while at Baden bei Wien and that Beethoven visited the spa many times. Later in the 19th century it became a stamping ground for operetta composers, and this period of time is the subject of Walzerseligkeit und Alltag: Baden in der 2. Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts (S950.c.9.324).

We learn from Ian Bradley’s Water music: music making in the spas of Europe and North America that Mozart composed his short motet Ave verum corpus while at Baden bei Wien and that Beethoven visited the spa many times. Later in the 19th century it became a stamping ground for operetta composers, and this period of time is the subject of Walzerseligkeit und Alltag: Baden in der 2. Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts (S950.c.9.324).

Baden-Baden was also the haunt of many musicians and writers. In 1860 Sir Charles Hallé, founder of Manchester’s Hallé Orchestra, wrote to his wife of spending the day with Berlioz and of meeting Wagner (Life and letters of Sir Charles Hallé being an autobiography (1819–1860) with correspondence and diaries). The town was also the setting for the novel Smoke by Turgenev who was a notable resident. A  detailed analysis of the growth of Baden-Baden to become by the 1860s the foremost German spa is presented by Karl Wood in his doctoral thesis Health and hazard: spa culture and the social history of medicine in the nineteenth century, based on documents in the town archives as well as on many contemporary guides. In addition to the draw of the cure, many spa guests were attracted by the social and leisure opportunities, one of which was the casino. Wood relates how opposition to gambling gradually grew and led to the casino being closed in the 1870s, not reopening until 1933.

detailed analysis of the growth of Baden-Baden to become by the 1860s the foremost German spa is presented by Karl Wood in his doctoral thesis Health and hazard: spa culture and the social history of medicine in the nineteenth century, based on documents in the town archives as well as on many contemporary guides. In addition to the draw of the cure, many spa guests were attracted by the social and leisure opportunities, one of which was the casino. Wood relates how opposition to gambling gradually grew and led to the casino being closed in the 1870s, not reopening until 1933.

As the popularity of spa resorts grew, many books were written by visiting doctors detailing the medicinal benefits. However, more general guidebooks also became available, for instance the 1856 book A first trip to the German spas and to Vichy (XIX.41.79) by the Irish scientist John Aldridge. He wrote engagingly of his travels, here describing taking the waters at Bad Ems:

The three Czech spas, also known in their time as Franzensbad, Carlsbad/Karlsbad and Marienbad, form the West Bohemian spa triangle. One very famous visitor to these parts was Goethe who made seventeen trips there. Several books have been written on his stays, the most comprehensive of which is Goethe in Böhmen by Johannes Urzidil (750:3.c.95.7). Later, King Edward VII chose to spend seven consecutive summers from 1903 to 1909 in Bohemia. The Austrian journalist Sigmund Münz was there each summer and had the opportunity to observe the King and his social connections at close quarters. Shortly before his death in 1934 he wrote up his recollections of this time and the many people he encountered in the fascinating King Edward VII at Marienbad: political and social life at the Bohemian spas (456.c.93.452).

The three Czech spas, also known in their time as Franzensbad, Carlsbad/Karlsbad and Marienbad, form the West Bohemian spa triangle. One very famous visitor to these parts was Goethe who made seventeen trips there. Several books have been written on his stays, the most comprehensive of which is Goethe in Böhmen by Johannes Urzidil (750:3.c.95.7). Later, King Edward VII chose to spend seven consecutive summers from 1903 to 1909 in Bohemia. The Austrian journalist Sigmund Münz was there each summer and had the opportunity to observe the King and his social connections at close quarters. Shortly before his death in 1934 he wrote up his recollections of this time and the many people he encountered in the fascinating King Edward VII at Marienbad: political and social life at the Bohemian spas (456.c.93.452).

The First World War marked a period of decline for spa resorts but the time of the Belle Epoque before this coincided with the zenith of spa culture. This can be seen reflected in the large number of guidebooks being published which the UL received under Legal Deposit. Here are a few examples:

We turn finally to the British representative, Bath, which was already a World Heritage Site in its own right since 1987 (for its Roman remains and Georgian architecture). “Oh! Who can ever be tired of Bath?” asks Catherine Morland, heroine of Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Austen was one of many famous authors who spent time in the city and Life & letters at Bath in the eighteenth century by Barbeau (479:7.c.200.8) gives insights into the experiences of many others.

Katharine Dicks

Further reading

- Water, leisure and culture: European historical perspectives edited by Susan C. Anderson and Bruce H. Tabb

- Aux sources de Vichy: naissance et développement d’un bassin thermal, XIXe et XXe siècles by Pascal Chambriard (328:8.a.95.1)

- Spa, carrefour de l’Europe des Lumières: les hôtes de la cité thermale au XVIIIe siècle edited by Daniel Droixhe, 2013 conference (C208.c.4225)

- Zur Kur nach Ems: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Badereise von 1830 bis 1914 by Hermann Sommer (570:01.c.70.48)

- Water, history and style: Bath World Heritage Site by Cathryn Spence (2013.9.826)