Political songs play an important part in popular culture and are powerful means of fostering and transmitting a sense of community and identity. Songs cross cultures and languages, as we discussed in an earlier blogpost on the French and American songs sung at the Liberation. On 14 July, Bastille Day, we want to shed light on another item from the Chadwyck-Healey Liberation collection: the Chants de la liberté (Liberation.b.130), a wonderfully illustrated collection of songs, accompanied by musical notation, which puts into perspective French political and historical struggles. Each song is accompanied by a didactic note, which provides some historical context.

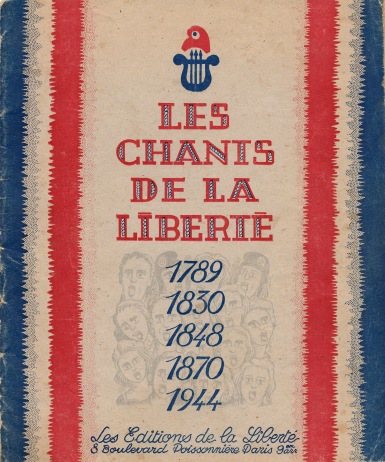

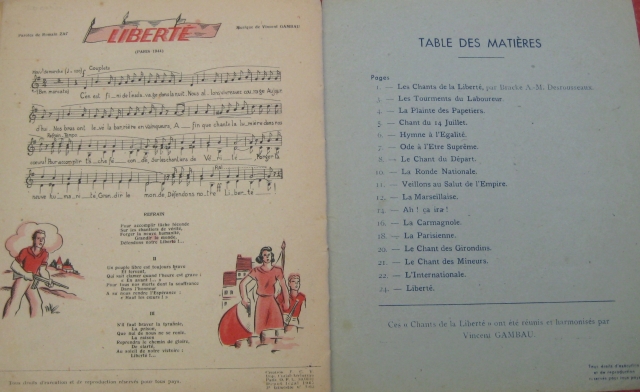

Les chants de la liberté 1789, 1830, 1848, 1870, 1944 / réunis et harmonisés par Vincent Gambau ; préface de Bracke A.-M. Desrousseaux ; illustrations de Robert Fuzier. Paris : Les Éditions de la liberté, 1945. (Liberation.b.130)

The title of the collection, which echoes the name of the publisher (the socialist Éditions de la liberté, well represented in the Liberation collection), places the Liberation of Paris at the end of August 1944 as the last of a series of revolutions in the history of France (brushing over the fact that the uprising led by the military resistant group FFI, French Forces of the Interior, could only be successful thanks to the arrival of the Allied forces). The editor and harmoniser, Vincent Gambau, specialised in popular, traditional and regional songs. The illustrator, Robert Fuzier, a member of the SFIO (Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière), participated in the Front populaire government in 1936. Engaged in the Résistance and in clandestine publishing, he was arrested in August 1943.

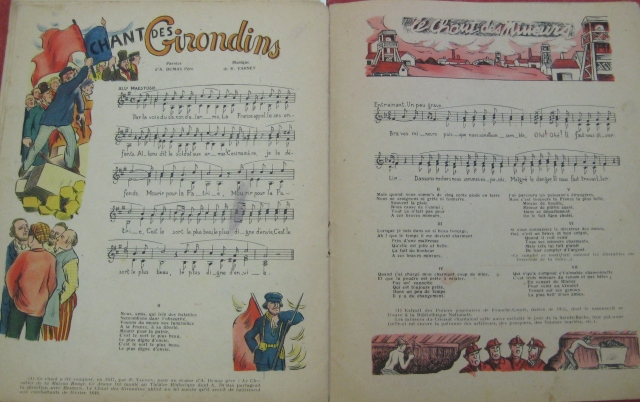

All the songs are illustrated, some in black and white, some in shades of red, and some multicoloured. The fonts of song titles show a great variety and have been designed with a attention to detail. The cover is printed on blue paper in blue and red ink. It features a harp, with strings made of arrows, surmounted by a Phrygian cap with a rosette, and shows a choir of men and women singing with their mouths open, some wearing the revolutionary hat.

The preface is by Alexandre-Marie Brake-Desrousseaux who was the son of the author of the Northern France nursery rhyme ‘Le P’tit Quinquin’ and an academic specialising in ancient Greek philosophy as well as a politician. He was a member of the French socialist party SFIO and the first translator into French of Rosa Luxembourg. During WW2, he was close to members of the resistance. He was arrested with his wife by the Gestapo on 27 June 1944, and imprisoned at Fresnes.

His preface immediately sets the tone because of its clear socialist orientation, with the use of the Marxist terminology of class struggle. The first songs in the collection, predating 1789, are the expression of workers, ploughmen (“Les tourments du laboureur”, from Brittany and Cornwall) and paper-makers (“La plainte des papetiers”, from Angoulème), “travailleurs du champ ou de la manufacture”.

A later related song in the compilation is “Le chant des mineurs” (1855). The collection of songs offers a sweeping tour of French history perceived in a dialectic frame. For Brake-Desrousseaux, after the “grande Révolution” of 1789, which gave power to the bourgeoisie, and the revolution of 1830 “volée à la République”, when the constitutional monarchy of Louis Philippe replaced that of Charles X (see “La Parisienne” by Casimir Delavigne), the bourgeoisie confronts “l’action prolétarienne” which succeeds in the creation of the French Second Republic in February 1848 (see the “Chant des Girondins” by A. Dumas père).

Quantitatively, songs related to the revolution of 1789 are the most numerous in the compilation: they include “Chant du 14 juillet; Hymne à l’égalité; Ode à l’être suprême; Le chant du départ; Ronde nationale; Veillons au Salut de l’Empire; La Marseillaise; Ah, ça ira !; La Carmagnole”.

The preface gives a prominent place to “L’Internationale” amongst the “hymnes militants et fraternels”, as the workers’ anthem, “pensée commune aux travailleurs de tous les pays”. The illustration shows strength and sobriety, due to the absence of colour and depiction of large homogeneous crowds demonstrating with guns or flags, on the foreground of modern architecture and smoking factories. This urban setting contrasts with the lower depiction of the “lendemains qui chantent”: the peaceful prospect of the sun rising on a pastoral landscape. Brake-Desrousseaux explains that its lyrics were written in 1871 by a member of the Paris Commune, Eugène Pottier. Its current music was composed in 1888 for a performance by a choir of workers from the city of Lille at a “Congrès syndical et socialiste à la fois”. Brake-Desrousseaux attributes the music to Adolphe Degeyter, while acknowledging the latter’s dispute with his brother Pierre Degeyter about the authorship of the song.

Le cerveau ouvrier parisien en 1871, le cerveau ouvrier en 1888 à Lille, ont assemblé les mots et les notes qui rassemblent, sur la planète Terre, les prolétaires résolus à l’action une pour l’affranchissement humain.

The song owes its worldwide success and dissemination to a number of key historical socialist events. Brake-Desrousseaux stresses that the hymn spread rapidly in France and Europe through important meetings of the “représentants du socialisme mondial”: the 1889 “Congrès des organisations socialistes françaises”, where it was memorably performed by the Lillois politician Henri Ghesquière, and the International Socialist congress held in Paris in 1900. The layout of the text and illustrations of the “Marseillaise”, placed at the centre of the book, is on the one hand very dynamic and expressive, and on the other hand balanced and harmonious.

The last song, “Liberté”, written by Romain Zac, in Paris in 1944, closes the gap between music composed on historical and contemporary events. It is an ode to victory, hope and freedom. Its illustrations show both a man carrying a gun and a woman holding a pistol. It places the whole collection in a spirit of liberation and optimism, as indicated in the preface:

Enfin, l’heure est venue où, de la clandestinité de sa naissance et de sa vie, va sortir fièrement à l’air libre le chant de Libération qui renouvellera dans les mémoires les serments de lutter pour l’avenir.

Irène Fabry-Tehranchi

Book looks great!!! Too bad no reprint in paper nor digital ebook., nor set of CD!! Alors! C’est

dommage!!!