Next week will mark the 500th anniversary of the death of Sebastian Brant (1458-1521), best known for his 1494 Das Narrenschiff (The Ship of Fools). This moral satire consisted of 112 chapters, each presenting a different fool and representing various examples of 15th century folly, all on a ship destined for the fictitious “fool’s paradise” land of Narragonia. While highlighting foolish behaviour of the time, Brant hoped to encourage his readers to recognise their own failings and to mend their ways. The first edition was printed in Basel by Brant’s friend Johann Bergmann von Olpe and crucially, at a time when few could read, featured woodcuts accompanying each chapter, some of which may perhaps have been by Albrecht Dürer. The depictions of fools, often wearing caps with bells or asses’ ears or holding a marotte, would have been familiar to contemporary readers.

Next week will mark the 500th anniversary of the death of Sebastian Brant (1458-1521), best known for his 1494 Das Narrenschiff (The Ship of Fools). This moral satire consisted of 112 chapters, each presenting a different fool and representing various examples of 15th century folly, all on a ship destined for the fictitious “fool’s paradise” land of Narragonia. While highlighting foolish behaviour of the time, Brant hoped to encourage his readers to recognise their own failings and to mend their ways. The first edition was printed in Basel by Brant’s friend Johann Bergmann von Olpe and crucially, at a time when few could read, featured woodcuts accompanying each chapter, some of which may perhaps have been by Albrecht Dürer. The depictions of fools, often wearing caps with bells or asses’ ears or holding a marotte, would have been familiar to contemporary readers.

The work became much more widely known in Europe after the publication in 1497 of Stultifera navis. This translation into Latin, the international language of the day, was carried out by Jakob Locher, a pupil of Brant’s, and it then became the basis for more adaptations and translations into several languages including 1509 translations into English. The drive to make it more accessible at a time when printing was still new and costly demonstrates how popular the work was, thanks in part to the important role that the images played. It could be described as an early bestseller.

Copies of the 1494 first edition are unsurprisingly rare, and Cambridge University Library does not hold one. Various digitised copies have been made available though including one held by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. The Latin translation was clearly more widely disseminated and many more copies remain. Our Special Collections holds three versions dated 1497 as well as a copy of the 1509 Alexander Barclay translation into English.

Copies of the 1494 first edition are unsurprisingly rare, and Cambridge University Library does not hold one. Various digitised copies have been made available though including one held by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. The Latin translation was clearly more widely disseminated and many more copies remain. Our Special Collections holds three versions dated 1497 as well as a copy of the 1509 Alexander Barclay translation into English.

As access to printed books is still somewhat limited I am relying here on more recent versions that can be viewed online, including a 2004 German version based on the original edition and edited by Manfred Lemmer and an English translation into rhyming couplets by Edwin H. Zeydel which he claims was the first English translation from the original text. Both feature reproductions of the woodcuts. Here are a few of my favourite “fools” who perhaps still have relevance to 21st century society:

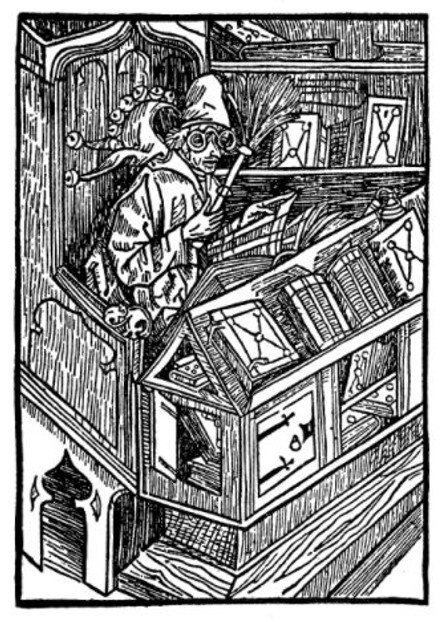

The very first fool in the book is the foolish reader who possesses many books but neither reads nor understands them, and is depicted keeping the flies off the pages.

Next we have the wealthy fool, appearing to value money more than wisdom as he counts his coins while a poor beggar sits in the foreground. Zeydel’s translation of the introductory text above the woodcut sums it up well:

Next we have the wealthy fool, appearing to value money more than wisdom as he counts his coins while a poor beggar sits in the foreground. Zeydel’s translation of the introductory text above the woodcut sums it up well:

The wealthy man of foolish creed

Who nevermore would beggars heed

Will be denied when he’s in need.

Brant patently valued keeping one’s counsel, saying that the man who stayed silent was wise whereas the man who talked too much was a fool. This is nicely illustrated in the text and woodcut by the idea that a noisy woodpecker can give away the location of its nest.

Brant patently valued keeping one’s counsel, saying that the man who stayed silent was wise whereas the man who talked too much was a fool. This is nicely illustrated in the text and woodcut by the idea that a noisy woodpecker can give away the location of its nest.

Another woodcut with bird imagery is the one for the foolish procrastinator. I am pleased to see that procrastination was as much a concern in the 15th century as it is now. The man who delays until tomorrow what he could or should do today will remain a fool and is described as someone who cries “Cras, cras” (Latin for tomorrow) like a raven.

Das Narrenschiff has been the subject of much scholarly research over the years, and most recently the focus of an impressive project at Würzburg University, the Narragonien Digital, making available ten early editions in an integrated online platform. After much work the final version of this is to be released on May 10, the anniversary of Brant’s death. On the same day some early editions can be seen at a collaborative show-and-tell event via Zoom between the Bodleian Library, the British Library and the Staatsbibliothek Bamberg. To find out more and to register please visit Oxford’s History of the Book blog.

Katharine Dicks

Thanks for the info on Sebastian Brandt – much appreciated and very informative.

Thanks to Jean Khalfa for the information that the first chapter of Foucault’s History of Madness is entitled Stultifera Navis, and takes Das Narrenschiff as its starting point.