This month, we look at three old and new books. Old to the Cambridge system but new to the University Library, the three anthologies offer interesting glimpses into the publishing world of the post-WW2 Stalinist period.

Hundreds of Slavonic books have recently started to be transferred to the University Library from the Modern and Medieval Languages Faculty Library (MML) as the MML makes space for new books coming in to support courses taught by the Department of Slavonic Studies. The history of the MML and UL’s Slavonic collections – a subject for a separate blog post – means that the former holds many early and Soviet literary editions which the latter lacks. As a result, we are taking close to 100% of the books they have withdrawn which are not already in the UL, and it is a pleasure to be able to add these books to our collections. Listed below are three examples from the Soviet period. In all three, the parental guiding hand of the state is very clearly seen, and a paternalistic Stalin features in many of the anthologised works.

Shkol’nyi teatr (School theatre; 9004.d.6439), 1947

This is a 525-page collection of plays for school-age children to put on. The spine of the book (shown right) lists the ten plays enclosed, some of which are adaptations of prose works. The text of each play in the volume is followed by a section of guidance for the director, and the book ends with two chapters containing general advice for actors and for “artists”. The last provides tips for those involved in production work, including a section which starts “Do not misuse stage make-up.”

On the reverse of the title page, the publishers describe the contents of the book (which is dedicated to the 20th anniversary of the formation of the Young Pioneer movement) as containing “a wonderful and courageous depiction of the young generation of our Soviet motherland.” Many of the young heroes in the anthology were so celebrated that they almost took on real life. Pavel Korchagin – the eponymous hero of one play (an adaptation of Nikolai Ostrovskii’s famous How the steel was tempered) – managed to stretch from fiction into fact when Soviet streets were named after him.

Chitaite, zaviduite, ia–grazhdanin Sovetskogo Soiuza (Read and be envious, I am a citizen of the Soviet Union; 9002.b.1841), 1950

This anthology contains poems by various Soviet poets. The preface credits the book’s wonderful name to the late Vladimir Maiakovskii (Mayakovsky) – the words of the title end his poem ‘Verses about a Soviet passport’. This poem is the first in the anthology, preceded only by the words of the Soviet national anthem. Many of the poems in the book are translations from Soviet languages other than Russian, from national languages such as Georgian and Estonian to smaller ones like Mordvin and Lezgian.

The book is divided into two sections. The first, and larger, focuses on the Soviet Union and its Communist values and achievements. The second looks at the rest of the world, underlining the injustice done in and by the capitalist West. Each section opens with an illustrated plate. In them, the artist (Naum Tseitlin) concentrates on the aspect of race, providing a happy, inclusive Soviet scene for the first section and a threatening scene of racism for the second.

Shakhtery (Miners; 9009.c.1599), 1950

A “literary-repertory collection”, Shakhtery provides prose, drama, poems, and songs on the subject of miners; the “repertory” part of the title indicates clearly that the content is designed for use in performance as well as for private reading. Anthologies of this kind were not uncommon in the Soviet Union. The publishing press which produced Shakhtery published similar collections, including one dedicated to oil workers in 1952.

The colophon at the end of the book tells us that our copy was one of 25,000 printed. How widely those copies were distributed and how heavily they were used we can only guess. Very few copies have made it into Western library collections, with only the Library of Congress and NYPL owning copies in addition to Cambridge.

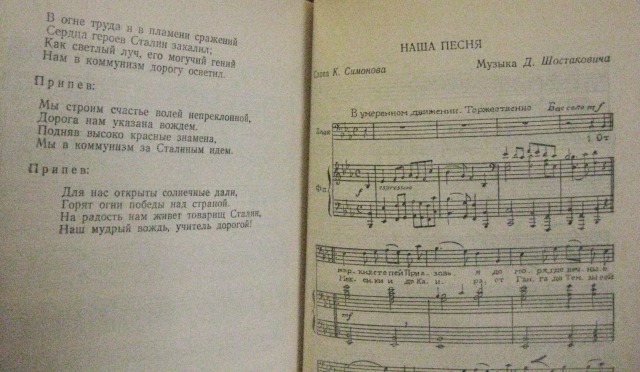

The anthology, as Read and be envious, starts with the text of the Soviet national anthem. There are 44 further pieces in the book, including eight songs:

- A song about Stalin

- Our song [a patriotic song with music by Shostakovich]

- The miner’s song

- The song calls us to great achievement

- Silver wedding : a comic song [the hero of the song is a miner]

- A colliery youth song

- The miner’s wedding song

- A song about the medal for miners

Mel Bach