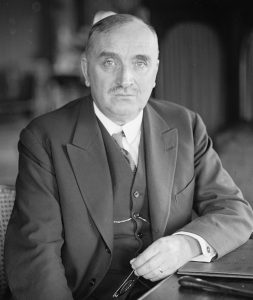

To mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of the poet and playwright Paul Claudel (1868–1955), a new exhibition in the Library’s Entrance Hall displays highlights from a collection of letters, postcards, verses and books sent or presented by Claudel to his friend and collaborator Audrey Parr (1892–1940), and donated to the University Library in 2001 by Parr’s granddaughter, Mrs L. M. Jack.

Claudel, who served in the French diplomatic corps, met Audrey, who was married to the British diplomat Raymond Parr, in Rome in 1915–16. The friendship deepened when both Raymond Parr and Claudel were appointed to Rio de Janeiro shortly afterwards. She and Claudel met intermittently thereafter, but pursued their relationship by letter. After the Parrs’ separation in 1930 Audrey settled in London, and remarried in 1938. She died in a road accident in May 1940.

Claudel’s letters and poems to Parr frequently show a whimsical, almost flirtatious, side to his character; he often signed with his pet name ‘Cacique’, and hoped that she might follow him around the globe. But beneath the light-hearted banter, the correspondence demonstrates the strength of an enduring friendship based on mutual passion for literature and the arts. The exhibition opens with the earliest surviving letter from Claudel to Parr, MS Add.9591/1, written during a mission to Washington in January 1919 (where, aptly for a French diplomat, he stayed at the Hotel LaFayette, whose letterhead he used). He told of his protracted journey to the United States via Martinique and Puerto Rico, and gave his impressions of New York. Claudel concluded the letter by recalling a walk he had taken with Parr by the Atlantic in Brazil, ‘while the big waves were breaking on the rocks’, during which she had confided ‘all her troubles’.

The two main printed items in on display both show the influence on Claudel of his diplomatic postings to the Far East, firstly to China in the 1890s and later to Japan in the 1920s. The prose poems in Connaissance de l’est were written in China and first published by Mercure de France in Paris in 1900. An enlarged edition appeared in 1907, and the work was reissued in China in 1914 as part of the ‘Collection Coréenne’ under the direction of the ethnographer, archaeologist and writer Victor Segalen (1878–1919). This edition was printed and sewn in oriental fashion, and its two volumes were housed in a fabric-covered wrapper. The Library’s copy, CCA.45.1, presented to Audrey Parr, is number 585 of 630 numbered copies.

In 1926–7, towards the end of a posting to Tokyo, Claudel wrote a number of short poems inspired by haiku, published as Hyakusencho = Cent phrases pour éventails (Tokyo: Koshiba, 1927). This edition of a hundred ‘phrases for fans’ was lithographed from versions which Claudel produced using a brush; the calligraphy of the accompanying Japanese characters, chosen as titles for their decorative and suggestive qualities, was the work of Ikuma Arishima (1882–1974). Three orihons, each consisting of numerous sheets of paper pasted together into a single length and folded in the style of a concertina, were housed in a chitsu, or wrap-around covering—a format already antiquated by the 1920s. The copy shown in the exhibition, CCA.45.3, was inscribed by Claudel for Parr in Washington in 1930, ‘in memory of the beautiful fans of Brazil’.

The exhibition pays particular attention to Parr’s role as a collaborator on Claudel’s creative projects. In Rio, she collaborated with Claudel and his secretary, the composer Darius Milhaud, in a ballet, ‘L’Homme et son désir’, for which she provided set designs. Milhaud later described how they cut fifteen-centimetre figures from coloured paper to work out the movements of the ballet. Claudel inscribed Parr’s copy of his play L’annonce faite à Marie, CCA.45.12, with a dedication to ‘my kind collaborator’.

Following ‘L’Homme et son désir’, Parr next collaborated with Claudel by producing illustrations for his poem Sainte Geneviève, published in Tokyo in 1923. Two years later, Claudel wrote Le vieillard sur le mont Omi, a set of prose poems, and asked Parr to illustrate the sequence; sheets from Claudel’s manuscript of the text, sent to Parr, with a page bearing a dedication, are included in the exhibition (MS Add.9591/188, ff. 1 and 3–4). It was decided that the artwork should take the form of paintings of butterflies. Several times in letters written between 1925 and 1927 Claudel expressed anxiety over delays to the printing of Le vieillard sur le mont Omi, and with increasing concern he asked after progress with Parr’s illustrations. In a letter from Tokyo of 6 January 1927 included in the exhibition, MS Add.9591/55, he underlined the question ‘And our butterflies, Margotine?’: Claudel feared they had flown away, taking the book with them.

In due course, however, the de luxe edition of Le vieillard sur le mont Omi was produced in Paris by Le Livre, illustrated with 30 gouaches by the illuminator and printmaker Jean Saudé after designs by Parr. Her original butterfly paintings, two of which are on display (MS Add.9591/188), were executed on a semi-transparent hot-pressed paper which allowed pigment on either side of the page to be visible: the edition had the subtitle ‘Papillons et ombres de papillons’ (‘Butterflies and shadows of butterflies’). Mrs Jack’s donation included a set of proofs, MS Add.9591/155, some folded as quires or bifolia, some with printed slips pasted on, and some with manuscript emendations. The butterflies were to be Parr’s last collaboration with Claudel, but their correspondence continued until just a few months before her death.

‘Paul Claudel and Audrey Parr: a friendship in books and letters’ runs in the Entrance Hall until 22 August, and can be visited during normal Library opening hours.

John Wells

Department of Archives and Modern Manuscripts