The 2021 Liberation Literature Lecture will take place online on Tuesday the 27th of April, 2021, from 6pm to 7pm UK time. Professor Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, the acclaimed art historian and exhibition curator, will speak on ‘Why the story changes : new understandings of art in occupied France’. Professor Dorléac’s talk and subsequent Q&A with Professor Nick White of Cambridge’s MMLL Faculty will be in French with simultaneous English translation. All are very welcome.

The lecture series is generously supported by the charitable trust of Sir Charles Chadwyck-Healey, who is of course also the donor of the extraordinary Liberation Collection which inspires the series.

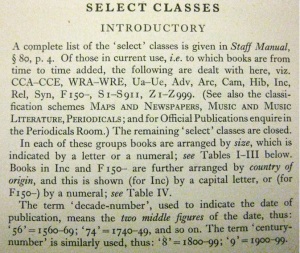

Among the artists who continued to produce work in occupied France (and who will be a focus in Professor Dorléac’s talk) was Pablo Picasso. The image shown here is the front cover of the Picasso libre exhibition catalogue which stands in the Chadwyck-Healey Liberation Collection at Liberation.a.232. The exhibition was held in the summer of 1945 at Galerie Louis Carré in Paris, showing paintings largely carried out under Nazi occupation before the Liberation of Paris in August 1944. The catalogue is large in terms of height (just under 29 cm) but brief: 63 pages of text and 21 plates. The plates are in black and white. I will update this post in due course with a couple of images when I am next in the Library. Current staff and students can look at an online version of the book via HathiTrust, through the temporary ETAS “check out” service: please see this other record in iDiscover.

Booking for the 2021 Liberation Liberation Lecture is now open, at this link [NB there is no need to enter a password, only an email address]. Further details about the event, in English and in French, can be found on this page, as well as contact details for the Library’s External Engagement team who are coordinating arrangements.

Mel Bach