The idea for this blog post came to me in 2021 when I read a review of an engaging new book, Charlie English’s The gallery of miracles and madness (e-Legal Deposit) in which I first learnt of Hans Prinzhorn’s Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (S400:05.b.9.337). This groundbreaking book analysed the artwork of disturbed psychiatric patients, with just over half of it devoted to detailed descriptions of ten artists, given pseudonyms to protect the reputation of their families. The book was first published 100 years ago in 1922; the University Library copy is a reprint from 1923, demonstrating the book’s popularity. In his The Discovery of the art of the insane (9000.b.1564) John MacGregor describes Prinzhorn’s work as “an unequaled contribution to the study of the art of the mentally ill.”

The idea for this blog post came to me in 2021 when I read a review of an engaging new book, Charlie English’s The gallery of miracles and madness (e-Legal Deposit) in which I first learnt of Hans Prinzhorn’s Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (S400:05.b.9.337). This groundbreaking book analysed the artwork of disturbed psychiatric patients, with just over half of it devoted to detailed descriptions of ten artists, given pseudonyms to protect the reputation of their families. The book was first published 100 years ago in 1922; the University Library copy is a reprint from 1923, demonstrating the book’s popularity. In his The Discovery of the art of the insane (9000.b.1564) John MacGregor describes Prinzhorn’s work as “an unequaled contribution to the study of the art of the mentally ill.”

Cover and title page of our 1923 edition (click on image to see enlarged): Prinzhorn demanded of his publisher that the cover be black with a runic font

Hans Prinzhorn (1886-1933) was uniquely placed to write this book as he had studied both art history and psychiatry. In 1919 he was taken on as assistant at the psychiatric hospital of Heidelberg University. A small collection of art and artefacts crafted by the mentally ill already existed there for the purposes of teaching and research; Prinzhorn was given the task of expanding the collection. Letters were sent out to the directors of psychiatric institutions and a large amount of work was sent back in response. By the time Prinzhorn left Heidelberg only two years later the collection numbered more than 5000 works by around 450 patients, most of whom had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. The original intention was that works would be returned but Prinzhorn realised the importance of keeping them together and hoped that the collection could have a permanent and accessible home. Charlie English suggests that while ultimately he “had failed in his ambition to create a physical museum, the book itself was a virtual art gallery.”

Prinzhorn was not the first person to write about the art of the mentally ill. Indeed, only one year earlier Dr Walter Morgenthaler had brought to attention the art of his patient, Adolf Wölfli, in Ein Geisteskranker als Künstler (2021 edition at C218.c.3940). But publication of Bildnerei der Geisteskranken certainly seemed to chime with the contemporary mood and aroused much excitement in the art world:

- Surrealists in Paris learnt of it when Max Ernst gave a copy to his friend Paul Éluard. The leading Surrealist, André Breton, who had himself attended medical school, wrote in his 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, probably after being exposed to Prinzhorn’s landmark text, “Les confidences des fous, je passerais ma vie à les provoquer” (I could spend my life prying loose the secrets of the insane)

- Paul Klee, teaching at the Bauhaus, had a copy in his studio and was much influenced by it

- The book made a huge impression on the young Jean Dubuffet who later founded the art brut movement.

After Prinzhorn left Heidelberg the collection continued to develop, and beween 1929 and 1933 some of the works were featured in a touring exhibition to German and Swiss cities. Sadly, some of the Prinzhorn Collection works were shown alongside the work of professionals in the Nazis’ 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition. Works continued to be added to the collection and these poignantly include pencil drawings by Wilhelm Werner which document the sterilisation procedure he was forced to undergo while a patient at Werneck asylum. In 1940 he was one of thousands murdered at Pirna-Sonnenstein as part of the Aktion T4 campaign. I learnt of his story at the Berlin memorial to victims of the Nazi euthanasia programme located at Tiergartenstrasse 4, site of the programme’s headquarters.

According to Charlie English the number of Prinzhorn Collection artists thought to have been killed by the National Socialists stood in 2020 at thirty (this number could rise as more wartime records opened up after German reunification are thoroughly investigated). Of the ten artists that Prinzhorn described in more detail in his 1922 book, at least half died before the Nazis came to power. One, however, definitely met the same fate as Wilhelm Werner. Franz Bühler (given the pseudonym Pohl) spent all but twelve years of his adult life in mental institutions before his 1940 murder at Grafeneck. As well as devoting 19 pages of his book to him, Prinzhorn also chose his Der Würgengel (The Angel of Death) for the plate facing the title page, indicating with this prominent position that this was a collection highlight for him. He even compared the work to that of earlier German masters:

Angesichts dieses Werkes von Grünewald und Dürer zu reden, ist gewiss keine Blasphemie.

(It is certainly not blasphemous to speak of Grünewald and Dürer in relation to this work)

After the war the Prinzhorn collection at Heidelberg was neglected, although we know that Jean Dubuffet visited it in September 1950 – this is documented in the 2015 exhibition catalogue Dubuffets Liste: ein Kommentar zur Sammlung Prinzhorn von 1950 (C201.b.9108). In the 1960s the collection was rediscovered by Dr Maria Rave-Schwank and restoration and research was carried out. Inge Jádi was appointed curator of the collection in the early 1970s and she was instrumental in raising awareness and exhibiting the works, deciding that enough time had elapsed that the pseudonyms could be dispensed with. In later years she shared the curation with the art historian Bettina Brand-Claussen. The culmination of Jádi’s work was the opening of a dedicated museum in 2001. Since 2002 Thomas Röske, whose doctoral thesis (Der Arzt als Künstler: Ästhetik und Psychotherapie bei Hans Prinzhorn, 326:3.d.95.146) was on Prinzhorn, has been director of the museum.

Prinzhorn’s book and collection remain important today and recent exhibitions and publications show the continuing interest. Here in Britain a selection of works were shown at the Hayward Gallery in 1997 and the UL has the accompanying catalogue: Beyond reason: art and psychosis: works from the Prinzhorn Collection (1997.11.4160).

A 2008 doctoral thesis (Alltag und Aneignung in Psychiatrien um 1900: Selbstzeugnisse von Frauen aus der Sammlung Prinzhorn by Monika Ankele, 326:3.c.200.711) considers the work of women in the collection, exploring their everyday life and behaviours through their artistic and personal testimonies as well as through medical records. It is important to note that in the early 20th century more than half of asylum patients in Germany were female but it is thought that fewer than 20% of the works Prinzhorn received were by women.

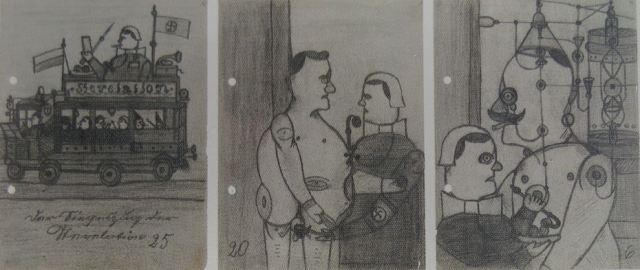

The UL’s newest relevant acquisition is Follement drôle = Wahnsinnig komisch (S950.b.202.652), the catalogue of a recent exhibition that was a collaborative venture between Sammlung Prinzhorn in Heidelberg and the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de l’Hôpital Sainte-Anne in Paris. The lower half of the cover features part of a 1924 work by August Klotz (Klett), another of the ten artists featured by Prinzhorn in his book.

The UL’s newest relevant acquisition is Follement drôle = Wahnsinnig komisch (S950.b.202.652), the catalogue of a recent exhibition that was a collaborative venture between Sammlung Prinzhorn in Heidelberg and the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de l’Hôpital Sainte-Anne in Paris. The lower half of the cover features part of a 1924 work by August Klotz (Klett), another of the ten artists featured by Prinzhorn in his book.

Katharine Dicks

Further reading

- Artistry of the mentally ill (400:05.b.95.104), 1972 English translation of Prinzhorn’s book

- The art of insanity: an analysis of ten schizophrenic artists, 2011 edition collecting the ten case histories which formed the core of the work, contains many black and white illustrations

- Artists off the rails, 2008 exhibition catalogue featuring the work of professional artists in the collection since the early 1900s

- Leibliche Bilderfahrung: phänomenologische Annäherungen an Werke der Sammlung Prinzhorn by Sonja Frohoff (199.c.72.226), 2015 doctoral thesis looking at the works of three artists from a phenomenological perspective

- Chapter in Kunst und Krankheit: Studien zur Pathographie (400:05.c.200.704), 2005 conference

- Bildnerei von Schizophrenen: zur Problematik der Beziehungssetzung von Psyche und Kunst im ersten Drittel des 20. Jahrhunderts by Jörg Katerndahl (S400:01.c.25.170), 2002 doctoral thesis

- Kunst & Wahn (S950.a.9.589), catalogue accompanying a 1997 exhibition in Vienna, includes a chapter on the wood sculpture of Karl Genzel (Brendel), one of Prinzhorn’s ten artists and a critical reading of Prinzhorn’s book

- Outsider art by Roger Cardinal (400:05.b.95.86) who writes about several of the Prinzhorn artists