16 May 2017 marks the centenary of Juan Rulfo, one of Spanish literature’s most revered and mysterious writers. Few other authors in any language have attained such mythic status on the basis of such a slim body of work. Rulfo is generally considered, along with Carlos Fuentes and Octavio Paz, to be one of the three most important figures of 20th Century Mexican literature. However, unlike the vast reams of prose and poetry written by his two compatriots, and their international standing as literary lions and esteemed intellectuals, Rulfo published very little and remained an ambiguous and elusive public figure.

Rulfo’s literary standing is based entirely on one collection of short stories (with the emphasis on “short”), El llano en llamas, and a slim novel entitled Pedro Páramo, published in 1953 and 1955, respectively. The spare, fragmented literary style of these two books and their dark, dream-like content has left them open to almost infinite possible interpretations, and their influence has loomed large over the last 60 years of Latin American literature. Until his death on 7 January 1986, Rulfo’s only further publication was a largely unheralded novella, El gallo de oro, in 1980, but his failure to definitively follow his two earlier masterpieces only served to bolster his legendary status.

The reality of Rulfo’s life and work was, of course, more complicated than the myth created around him, and in some ways created by the man himself. He was relatively privileged, hailing from a family of wealthy landowners and able to rely on them for financial support for much of his life, but also the victim of great misfortune and suffering, losing his parents and other family members in the brutal aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. Similarly, he was lacking in the formal education and intellectual background of most of his literary peers but read voraciously and widely, gaining deep, albeit self-taught, knowledge of literature and history from around the world.

Rulfo often presented himself as an “elemental” autodidact, which was very much in keeping with the uneducated rural characters who he mostly wrote about, and was deliberately vague and obfuscatory regarding the exact details of his life and literary touchstones. For example, the influence of William Faulkner – a far closer point of comparison to his work than most of his Latin American contemporaries – on Rulfo is a source of ongoing debate. He claimed never to have read the Southern US author until he started to see their respective work compared, but the similarities between, say, the opening story of El llano en llamas, Macario, and The Sound and the Fury, or Pedro Páramo and As I Lay Dying are surely too marked to be purely coincidental.

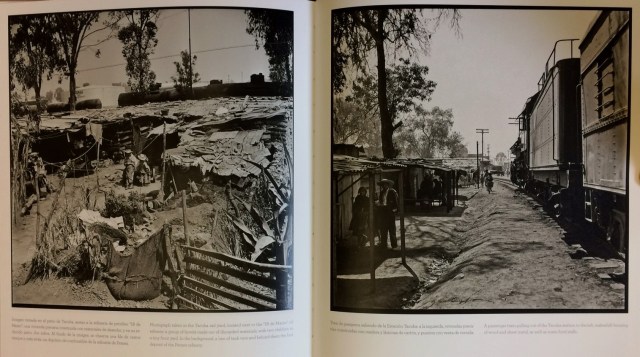

As well as many similarities in writing style, Rulfo shared with Faulkner a sympathy for dispossessed and marginal characters and a desire to convey their suffering and struggles. The landscape of Rulfo’s fiction is based on the rural Jalisco of his childhood and conveys the devastation wreaked on it and other Mexican regions by the country’s post-Revolution secularization and industrialization, and the Cristero Wars that followed. As well as witnessing this environment first-hand while growing up, it also impacted Rulfo directly through the violent death of his father in 1923.

The lives of Rulfo’s characters are utterly bleak and devoid of hope. They lead ghostly, disconnected existences and, in the case of Pedro Páramo, they do seem literally to be ghosts. One of Rulfo’s great talents was the ability to enter completely the tortured and often incoherent mindsets of these characters. Whenever he returned to the countryside from his later homes in Guadalajara and Mexico City, he was said often to talk at great length with local farmers and labourers about their way of life. Perhaps not coincidentally for one so deeply immersed in this bleak and hopeless milieu, Rulfo also shared William Faulkner’s struggles with mental illness and alcoholism. These may have contributed as much to his later lack of productivity as any premeditated desire to leave behind a small, perfectly formed body of work.

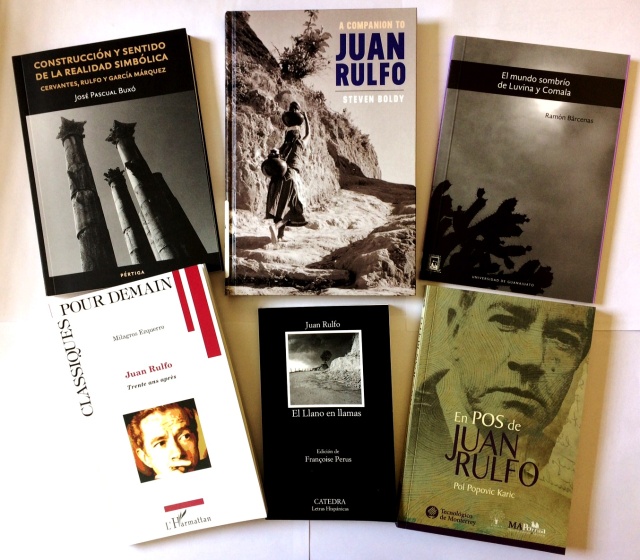

The UL has collected material by and about Juan Rulfo from the very start of his international literary acclaim in the 1960s. Our earliest holdings are a first edition of Pedro Páramo, and an early copy of El llano en llamas donated by the Mexican government – Rulfo’s works were first published by the Fondo de Cultura Económica, a non-profit, partially government-funded publishing group. Since these were first published, scholarship surrounding Rulfo has grown exponentially, even more so since his death, and in the last 10 years alone the UL has obtained nearly 30 titles in a variety of languages related to Rulfo and his work.

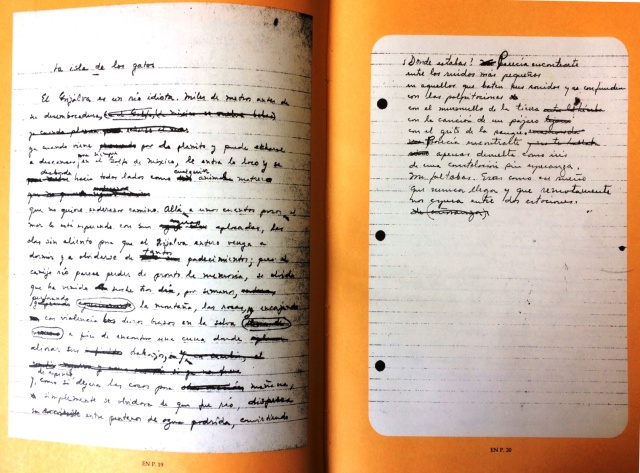

However, unlike other authors of his stature, relatively little new material by Juan Rulfo has emerged posthumously. In terms of written material, only his letters to his wife and notebooks have been published, while the reputed existence of unpublished fictional works is still disputed to this day. Rulfo was also an avid and accomplished photographer, dealing with similar subjects to his fiction, and there are some particularly interesting recent publications (e.g. this and this) focusing on the visual side of his work.

We are fortunate enough to have one of the world experts on Rulfo here at Cambridge in Professor Steven Boldy, and his recently published Companion to Juan Rulfo is the ideal introduction to the author and his small, but infinitely rich oeuvre.

Christopher Greenberg