On 21 November 1811 the celebrated German writer Heinrich von Kleist killed himself and his close friend Henriette Vogel in a double suicide pact. Not eligible for church burial, they were buried at or close to the place where they died, by the Kleiner Wannsee lake between Berlin and Potsdam. I stayed near here in the summer, and as my daily walk to the S-Bahn station took me past a sign to the grave I was moved to visit it.

By autumn 1811 Kleist had reached a crisis point of desperation, feeling mentally exhausted with financial worries and aggrieved that his work was not appreciated by his contemporaries. Since autumn 1810 he had been editing a short daily (except Sundays) newspaper, the Berliner Abendblätter (facsimile edition can be viewed at archive.org). Readers had particularly lapped up the police reports published in it which Kleist received from his friend Justus von Gruner, police chief of Berlin. But when von Gruner was dismissed, this source dried up and Kleist was forced to fill his paper with news stories reprinted from other papers. Interest soon dwindled and this, combined with a tightening of censorship regulations, led to the publication being discontinued in spring 1811. Kleist’s crisis was intensified by his friendship with Henriette Vogel. The pair had met two years earlier and she had subsequently fallen into a depressed state and craved death after being given a cancer diagnosis.

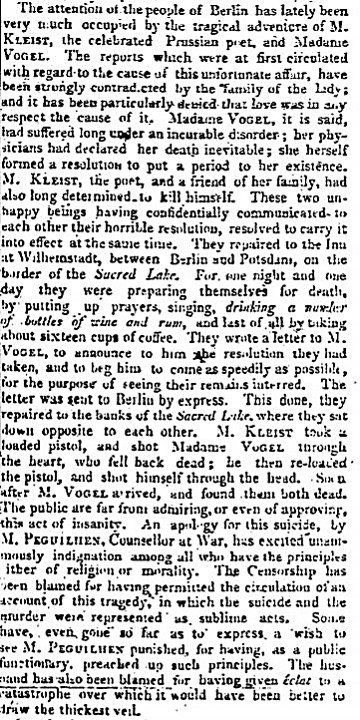

The news of Kleist’s untimely death at the age of 34 made it into newspapers across Europe, including The Times newspaper, although not until a month later on 28th December:

More recently the somewhat unclear circumstances surrounding his death have inspired new works of literature and film in Germany and further afield:

More recently the somewhat unclear circumstances surrounding his death have inspired new works of literature and film in Germany and further afield:

- In the 1980s Karin Reschke gave voice to Henriette Vogel, a name relegated to the margins, in Verfolgte des Glücks: Findebuch der Henriette Vogel (748:39.d.95.101).

- In 2002 Henning Boëtius wrote a fictionalised version of the events in his novella Tod am Wannsee (C202.c.6772) with illustrations by Johannes Grützke.

- In 2018 the French novelist Patrick Fort produced the novel Le voyage à Wannsee (C205.d.6540) in which a fictional account is blended with source documents to provide a moving tribute to German romanticism through the figure of Kleist.

- The 1969 German film Wie zwei fröhliche Luftschiffer(Like Two Merry Aeronauts) dealt with the last three days of Kleist’s life, drawing on Kleist’s letters and other documentary material from preceding years for much of the text.

- Amour Fou (2014), an Austrian film, also tells the story of the last months of Kleist and Vogel. The suggestion is made that Henriette Vogel was not Kleist’s first choice to die alongside him. The film also suggests that her symptoms had psychological causes and an autopsy after her death reveals that she had no tumour.

The grave site itself has an interesting and rather chequered history, and it is quite likely that the memorial stone no longer marks the exact place of death or burial. At the time of his death Kleist was not particularly well known but nevertheless curious tourists visited, probably fascinated by the rumours of a love affair between Kleist and Vogel. The site was neglected and became overgrown but in 1848 a granite memorial stone was erected for the first time. During the 1860s the poet Max Ring led a public appeal for funds to improve the site, which enabled a marble panel to be added on which a verse by Ring was inscribed:

Er lebte, sang und litt

in trüber, schwerer Zeit,

Er suchte hier den Tod

und fand Unsterblichkeit.

[He lived, sang and suffered in gloomy difficult times, he sought death here and found immortality.] This was accompanied by a reference to Matthew Ch. 6, v. 12 which is the line “Forgive us our trespasses…” from the Lord’s Prayer. Railings were also erected around the grave.

During the late 19th century the surroundings of the grave site changed as villas were built nearby and what had been a small hill sank down due to extraction for clay by a neighbouring brickworks. In 1904 the land was in the hands of Prince Friedrich Leopold of Prussia but he gave it to the nation. To coincide with visitors coming to Berlin for the Olympic Games, an overhaul took place in 1936 – the original memorial was replaced by a new granite stone onto which Ring’s verse was transferred (the marble panel being moved to the Märkisches Museum). But in 1941 the words of the Jewish poet were chipped off and replaced by a quote from Kleist himself:

Nun, o Unsterblichkeit, bist du ganz mein

[Now, immortality, you are all mine] from the play Prinz Friedrich von Homburg.

Left: 2009 view (Jochen Teufel via Wikimedia Commons), right: 2019 view (Danny Dicks)

For almost 200 years Henriette Vogel’s death was not marked at the site but this was rectified in 2003 with a small simple memorial stone. Then finally in 2011, to mark the 200th anniversary of their deaths, a grand redevelopment was undertaken. The granite stone has been turned through 180° with Ring’s verse restored to the front accompanied by the names and dates of both Kleist and Vogel, with the Kleist quote now on the back. The railings have been restored, new information boards are in place and the area has been landscaped with new paths to reach the memorial from the main road. At last Kleist, the famous writer, has a suitable tribute.

Katharine Dicks

Bibliography

- Bisky, Jens: Kleist: eine Biographie (2007, 747:32.c.200.76)

- Bisky, Jens: “Küsse, bisse” (2010, T746.c.1.93)

- Blamberger, Günter: Heinrich von Kleist: Biographie (2011, 747:32.c.201.1)

- Blankenagel, John C.: “The London Time’s Account of Heinrich von Kleist’s Death”, Modern Language Notes, vol. 47, no. 1, 1932, pp. 12-14 (online on JSTOR)

- Minde-Pouet, Georg: Kleists letzte Stunden. Teil 1: Das Aktenmaterial (1925, 746:01.c.1.2)

- Müller-Lauter, Erika: “Geschichte des Kleist-Grabes”, Kleist-Jahrbuch 1991, pp. 229-256 (P746.c.301.6)

This has been very touching. I am curious though as to the identity of the person he originally had in mind to share in this immolation. Do you know?

According to Amour Fou it was his cousin Marie but I’m not sure if there is any evidence for this.